The Findhorn Foundation: Myth and Reality

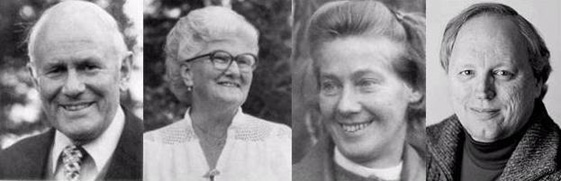

l to r: Peter Caddy, Eileen Caddy, Dorothy Maclean, David Spangler

CONTENTS KEY

- The Rosicrucian Peter Caddy

- Sheena Govan, Eileen Caddy, and Roc

- Findhorn Bay Caravan Park

- David Spangler plus Limitless Love and Truth

- Peter Caddy Exits and Eileen Caddy as Community Figurehead

- Esalen Influence and the Grof Phase

- The 1990s and Economic Problems

- The Real Situation of Eileen Caddy

- Conflict Resolution a Farce

- Peter Caddy Endorses a Dissident Book

- Pierre Weil, NGO Status, and Peace Anomaly

- Crises of Holotropic Breathwork

- Toeing the Party Line of Suppression

- Unconditional Love and the Testimony of Howard Whiteson

- Perfect Peace in Question

- The Analysis of John Greenaway

- Sir Michael Joughin as Sceptical Observer

- Ecovillage Ambition and the Heavy Debt

- Commercial Workshops and the Affluent Lifestyle

- Ecobiz

- Vatican of the New Age

- Bill Metcalf and the Internet Stigma

- Findhorn Press and the Angel of Findhorn

- Elite Celebrities of the Foundation

- "Who I Really Am" and Creative Chaos

- Dissident Stephen Castro

- CIFAL Findhorn Ltd

- CIFAL and Consultancy Workshops

- Local Actors and Legal Complexities

- UNESCO Problem

- CIFAL and the Business Park Workshop Programme

- Suspending Judgment can be a Hazard

- Dangers Inherent in Extremist Affiliations

- Criticism from Chris Coates

- Theologian John Drane in Contention

- The Troll Factor

- Bibliography

PART ONE: THE EARLY YEARS, CONCEPTUAL INFLUENCES, "MAGIC OF FINDHORN" PROMOTIONALISM, AND ANOMALIES

The Times online obituary for Eileen Caddy (1917–2006) described the subject as an “unconventional spiritualist” who helped to found the “Vatican of the New Age,” a nickname conferred upon the Findhorn Foundation (existing in Moray, north Scotland). The nickname may be significant in a manner not intended by the glorifiers. Some strong repressive measures, associated with religious orthodoxy, adhere to the unofficial history of the Findhorn Foundation.

Beginning in 1962, the Findhorn Foundation was originally a caravan site in the dunes alongside the Moray Firth. That site became known as the Findhorn Community, not to be confused with the village of Findhorn nearby, whose inhabitants came to resent the conflation of identities. Three and a half decades later, the Findhorn Foundation gained the status of an NGO (Non-Governmental Organisation, associated with the United Nations). A drawback is that the history of these developments has not been comprehensively charted, despite various popular treatments of the subject by partisan writers like Carol Riddell and Alex Walker. The Times online version settles for some beaten track details along with one or two phrases that are perhaps slightly cynical.

The other major co-founder, Eileen Caddy’s second husband Peter, was appointed manager of the Cluny Hill Hotel, at Forres, prior to the more famous caravan site phase at nearby Findhorn. In his hotel role, Peter Caddy “turned to Eileen for guidance that seemed sometimes absurdly banal: for example, her inner voice advised him to charge £10 extra for an extra bathroom and to give the Duke of Bedford the best room” (Times online obituary).

Critical analysts are not obliged to credit a blithe partisan statement: “For five years God, one might say, via Eileen’s [inner] voice and Peter’s administration, became a hotel manager” (Riddell 1991: 73). The theme of God as a hotel manager (during 1957-62) is one of many superfluities found in the enthusiast reports promoted by Findhorn Press, the Foundation publishing arm. Carol Riddell joined the Foundation in 1983; her book subscribes to the notions and jargon of the canonical format.

1. The Rosicrucian Peter Caddy

Peter Caddy (1917–1994) was born into a middle class Methodist family in Middlesex. He was educated at Harrow. During his boyhood, Caddy was introduced to Spiritualism, his father being a sufferer from rheumatoid arthritis who attended the weekly séances of Lucille Rutterby in the hope of a cure. Rutterby was a Spiritualist medium and “healer” who claimed to transmit messages from a spirit guide named Silver Deer. The dominant craze amongst Spiritualists at that time was “North American Indian” spirit guides, who always spoke in English.

In his late teens, after obtaining an apprenticeship with a catering firm, Peter contacted an organisation which exerted a strong influence upon him. This grouping he believed was “a fellowship of the original Christian Rosenkreutz Rosicrucians.” That belief amounts to a popular occultist misconception. The original group of “Rosicrucians” were Lutheran radicals associated with the pastor Johann Valentin Andreae; they are discussed in recent scholarly literature. Those religious radicals were not as the subsequent occultist grapevine chose to depict them some three centuries later (Shepherd 2004:218–19).

An enthusiast report states that Peter Caddy came “under the tutelage of one Dr. Sullivan” (Hawken 1975:52). This entity was the amateur actor and playwright George A. Sullivan (1890–1942), who used the pen names of Alexander Matthews and Aureolis. Sullivan left the Theosophical Society along with Mabel Besant-Scott (the daughter of Annie Besant), who failed to succeed her mother as leader in the status stakes. During the early 1920s, Sullivan created the Rosicrucian Order Crotona Fellowship, lasting for some thirty years. This was a relatively small grouping. Sullivan published pamphlets arising from his correspondence course. The Fellowship indulged in extravagant Rosicrucian lore already popular within the Theosophical Society; they also employed quasi-Masonic rituals (Sullivan being closely associated with a co-Masonry order founded in the 1890s). About 1935, Sullivan moved to Christchurch (Dorset). In 1938 he tried to gain more subscribers for his eccentric project by opening a private theatre, teaching his form of Theosophy via drama. He finally staged “vaudeville and musical comedy in a last desperate attempt to attract audiences” (Hutton 1999:213).

Sullivan had adopted the status title of “Supreme Magus.” The young Peter Caddy came to regard him as a “being of vast knowledge,” gaining entry to the London-based branch of the Fellowship, also travelling regularly to Christchurch to attend the “Rosicrucian” gatherings. Caddy’s autobiography relates his belief that Sullivan possessed an esoteric cipher manual of Sir Francis Bacon, handed down the generations by “Rosicrucian” masters (Sutcliffe 2003:42–3). Peter Caddy's description of Sullivan can evoke incredulity:

Doctor Sullivan was what is called in esoteric circles a Master, being the head (or Supreme Magus) of the Rosicrucian Order, Crotona Fellowship, which had chapters all over Britain. This Order had grown out of the original Rosicrucian mystery school which could trace its roots back to medieval Europe and beyond.... When Doctor Sullivan wrote and lectured, he often went back in time, recalling other incarnations (past lives in the world). He could travel to anywhere he wanted on the inner planes of reality. He was always examining our progress, whether he was there in person or not. Francis Bacon had written a code and cipher book for all the secret messages that had been hidden throughout the plays of Shakespeare; Doctor Sullivan had that original book, and I have seen it. (Caddy 1996:31-32)

The misleading ideas about Francis Bacon, in these circles, doubtless serve to explain references to that British philosopher in “channelling” lore, attendant upon the early 1970s lectures of David Spangler at Findhorn (cf. Walker 1994:406ff). One report strongly indicates that, in his later years, Caddy believed himself to be the successor to Sullivan as “Rosicrucian Master” (Akhurst 1992:34; Castro 1996:30).

2. Sheena Govan, Eileen Caddy, and Roc

During the Second World War, Peter Caddy served as a catering officer in the RAF. Afterwards, while stationed in Iraq, he met Eileen Combe (later Caddy), whose first husband was also a RAF officer. Eileen had become familiar with Moral Rearmament, an evangelical Christian movement associated with Frank Buchman. Her first husband was an exponent of the doctrines involved; she participated in the “guidance” sessions. “Her husband became obsessed by Moral Rearmament and imposed its disciplines on her, which she found increasingly restrictive” (Times online).

Her husband attempted to convert Peter Caddy, who appears to have been more interested in Eileen. “Their relationship remained platonic until 1953” (ibid), after she returned to England. Eileen Combe then proposed a divorce from her first husband. She was banished from the family home (and her five children) by her husband, who was still in Iraq. Peter Caddy's second wife Sheena Govan now “ostensibly welcomed her into the marital home in London” (ibid), although the situation did not prove easy. The Rosicrucian adept Peter Caddy had created a volatile situation of ménage à trois.

Sheena gained a reputation for being authoritarian and irascible. Her flat in Pimlico was the venue for a small early 1950s circle which entertained “esoteric” influences surfacing in middle class sectors. The jargon of Sheena’s group included usage of the confusing phrase “new age,” chiefly associated with Alice Bailey (1880–1949), whose Arcane School elevated the elusive Tibetan Djwal Khul in a Theosophical manner. Bailey’s book Discipleship in the New Age (1944) is a glamorous portrayal of the anticipated Aquarian transition. The beginning of “new age groups” has been dated to the 1930s (Sutcliffe 2003:51). "New age" phenomena are more commonly associated with the 1960s emergence of diffuse popular beliefs and organisations, frequently failing to impress observers that any solution to "Old age" problems is being provided.

The Caddy departure from Theosophy found a more tangible mouthpiece than the invisible Djwal Khul. Eileen Caddy first heard the desired “inner voice” in 1953 at a church in Glastonbury. “Be still … and know that I am God” (Hawken 1975:71). She later referred to the voice as “an instrument from the God within us all.” She was strongly influenced in this commitment by a rather contradictory situation, in which she effectively competed for the full attention of Peter Caddy prior to their marriage. Eileen became the disciple of Sheena Govan, the second wife of Peter whom she (Eileen) actually replaced in matrimony.

Sheena claimed inner messages and stressed the “Christ within.” In her London apartment, Sheena held groups and taught that “the true teacher was within each one of us” (Sutcliffe 2003:59). The reliability of such teachings is in question, the precepts having frequently instilled a sense of complacent accomplishment in those disposed to believe that they are true teachers. The situation under discussion is made more problematic by Eileen’s statement in her autobiography that she obeyed Sheena through fear and the desire to please Peter. Indeed, Eileen even states that she hated Sheena (Caddy 1988:34).

Peter and Eileen Caddy

Sheena Govan passed out of favour by 1957, when the newly married Eileen and Peter Caddy moved to Scotland, ending up at Cluny Hill Hotel that same year. Sheena quickly vanishes in the Riddell version of events. What actually happened? Sheena had married Peter in 1948, but he had transferred his affections to Eileen. In 1957, information about Sheena and Peter Caddy leaked out in a newspaper, proving an excuse for Peter to jettison contact with Sheena. “In the space of a few months Sheena had been transposed from guru of the Chelsea Embankment to Celtic witch” (Sutcliffe 2003: 63).

The segregation continued when, in the early 1960s, Sheena went to live at a village close to the new Findhorn Community. She visited the nascent community, where the Caddy attitude towards her is reported to have been curt. Peter wrote that she had failed in her mission, so contact with her had terminated. Eileen’s autobiography is similarly dismissive of the intruder, resorting to the “inner voice” sanction of segregation: “My beloved child, the past is past and finished.” Sheena died from a cerebral haemorrhage in 1967, poor and neglected, while occupying a rented house in Kirkcudbrightshire (Sutcliffe 2003:64). While God became a hotel manager at Cluny Hill, elsewhere the witch died in ignominy. Eileen became closely associated with the new age theme of unconditional love.

Meanwhile, at Cluny Hill Hotel, Eileen continued to give “guidance.” Peter became preoccupied with the prospect of UFOs, emphasising visits to the local beach for sightings. Unidentified Flying Objects are not the most reliable subject. Peter Caddy explains how his hobby at Cluny Hill was sustained in a bizarre manner he never questioned:

Eileen had seen with her inner eye the word LUKANO written in letters of fire. Since neither of us knew what it meant, we were told to write and ask Naomi, who was a remarkable sensitive and could be in instant telepathic contact with any name given to her, whomever it belonged to. She was in immediate contact with the being called LUKANO, who said that he was the captain of a “mother ship” from Venus and wanted to make contact with us, because mankind was in great danger…. Over the next few years, therefore, we were in daily contact with those [extraterrestrial] beings through Dorothy [Maclean], Lena, Eileen and later Naomi. (Caddy 1996:161)

The psychic messages of “guidance” gave a continual running commentary, informing that two spaceship landings were attempted near Cluny Hill Hotel in 1960-61. The failure was explained by the eloquent psychics in terms of “climatic conditions and, more importantly, the radiation from a recent atomic text explosion in the atmosphere” (Caddy 1996:166). Awaiting a third attempt, “Lena and I – and sometimes Eileen – would patiently keep vigil on the landing site at one o’clock in the morning” (ibid).

After these fantasies, Peter Caddy was easily influenced by his friend Robert Ogilvie Crombie (alias Roc), who gained a reputation for exotic statements and experiences. At his Edinburgh apartment, Crombie "became aware of a being in what looked like a spacesuit, sitting in the chair opposite him" (Caddy 1996:256). Afterwards, the same being stood at the foot of his bed, saying: "I'm from Venus - and what are you going to do about it?" (ibid).

Crombie (Roc) was described by Sir George Trevelyan as one of "the great pioneers of the New Age" (Caddy 1996:345). Crombie was persuasive in the early years of the Findhorn Foundation, being described by Peter Caddy as "the community's mentor" (Caddy 1996:344), prior to his death in 1975. The gullible Rosicrucian relays: "It was his [Crombie's] connection with St. Germain, the Master of the Seventh Ray, that I esteemed most highly" (ibid:258).

In 1966, Crombie accompanied Peter Caddy and esoteric enthusiast Kathy Sparks on a two week journey in England and Scotland. Caddy reports: "It appeared that the main purpose of our trip was to discover and 'cleanse' the ancient network of power centres that are dotted throughout Britain.... the 'cleansing' would happen by Roc anchoring through his body into the ground what he experienced as a magenta ray of light" (Caddy 1996:260).

The Caddy background was middle class, a factor which does not exclude superstition, well attested in similar instances. Eileen had been born in Alexandria, Egypt, where her father (a director of Barclays Bank) had a luxury home set in a large garden suited to British colonial outdoor parties.

Eileen had learned from Sheena a schedule of daily meditation and writing, “in order to pick out ‘God’s voice’ among the many different conversations she heard in her head” (Sutcliffe 2003:68). There are strong critics of this practice, possessing affinities with the Faith Mission and Moral Rearmament. Sheena had been affiliated to the former in her childhood (ibid:56–7), while Eileen had participated in Moral Rearmament “guidance” sessions that she later acknowledged as formative influences. There are many other meditation formats, quite different to that of Sheena and Eileen, which do not resort to evoking any inner voice.

In November 1962, the Caddys moved with their three children to the caravan site near Findhorn, after their exit from Cluny Hill Hotel. They lived on National Assistance and child allowance. The introspective Eileen does not appear to have been very strong; even a brief trip into nearby Forres made her feel “weak and shaken” (Sutcliffe 2003:78). The more energetic Peter worked on a vegetable garden, a project in which he was influenced by the assertions of Dorothy Maclean, a Canadian colleague and third co-founder of the ensuing community. Maclean claimed to communicate with “devas and nature spirits.” As a consequence, Peter believed that he gained the aid of a “deva” or angelic being in his horticultural endeavour.

However, gardening was not a sufficient outlet for the drive of Peter Caddy. In 1965 he was busy travelling about to various “spiritual centres” in Britain, in this way encountering Sir George Trevelyan (1906–1996), whom Caddy called “the father of the new age in Britain” (Sutcliffe 2003:80). Trevelyan controversially inserted alternative spirituality into his teaching courses at Attingham Park (upon his retirement in 1971, he founded the Wrekin Trust, subsequently to be associated with the organisation known as the Scientific and Medical Network). Influenced by writers like Rudolf Steiner and Alice Bailey, Trevelyan later wrote A Vision of the Aquarian Age (1977), a work which found critics.

More influential was Marilyn Ferguson’s The Aquarian Conspiracy (1982), bringing the alternative term “Aquarian” into a more popular ambience. One assessment states that the evocative term “rang of the 1960s, not the 1980s; entertainers in the 1960s from the Beatles to the cast of the rock musical Hair had celebrated the coming of the ‘Age of Aquarius’ ” (Raschke 1996:214). The question as to which new age exponents and gurus are entertainers is still very relevant, even though the issue is too often mystified.

Peter Caddy was definitely a new age enthusiast. When in 1965 he attended a meeting at Attingham Park, he rubbed shoulders with Trevelyan and various “new age group leaders” (Sutcliffe 2003:82). Caddy made the most of that occasion; via his subsequent liaisons, he placed the Findhorn caravan site on the map for a wave of enthusiastic visitors during the late 1960s. Trevelyan himself made a visit in 1968; he is reported to have been enthusiastic about Caddy’s garden. That subject became a rather extravagant topic, encouraged by Caddy and his associate Robert Crombie.

In 1971 appeared Eileen Caddy’s God Spoke to Me, the title attesting an emerging belief about her significance. The “divine guidance” was commemorated in Findhorn News, the early organ of the Findhorn Community, edited by Peter. Eileen’s guidance was here constantly used as support for the contents. Her autobiography identifies the deific “Me” in her messages as “your own inner God” (Sutcliffe 2003:80). Her husband conducted the daily organisation of the nascent community (Castro 1996:2). Peter’s industrious liaisons with the growing “new age” sector ensured that his isolation and poverty terminated. In 1969, the formerly obscure caravan park is said to have received more than 600 visitors. An appeal to build a bungalow for the Caddys quickly raised £3,500 (Times online), quite a lot of money in those days. Trustees were appointed for a charitable trust.

An enthusiastic commemoration appeared in The Magic of Findhorn (1975), written by the American journalist Paul Hawken. This book was the first commercial publication about the new community, and markedly glorifying. An academic commentator describes this work as promoting “a miraculous image reminiscent of the ‘signs and wonders’ theology of conservative evangelical Christians” (Sutcliffe 2003:79). A rubbish dump (Peter Caddy’s horticultural plot) was depicted by enthusiasts as becoming a Garden of Eden. New age fantasies were prolific thereafter.

The crops in the Garden included a reputed forty-two pound cabbage. Roses were said to bloom in the snow. The sandy soil of the Moray Firth is not the most hospitable terrain. Caddy removed the sand on his ground. The supposed miracle, attributed to deva benevolence of the Maclean lore, is undercut by the data that Peter Caddy used ample compost (plus dung and seaweed) in his small plot. Further, Durham Agricultural College grew a seventy pound cabbage in 1988 with the aid of generous manures (Castro 1996:4).

4. David Spangler plus Limitless Love and Truth

In 1970, the new age influx of visitors included the young American David Spangler, then in his twenties, who returned the following year to settle. His three years of residence imparted a new direction in terms of American trends and idioms associated with the Human Potential Movement. One of Spangler’s associates introduced “counselling” into the community, the harbinger of alternative therapy. The craze known as “channelling” was the major preoccupation of new wave Community members.

Soon after his first arrival, Spangler began to claim an ability to “channel” Limitless Love and Truth, thus rivalling Eileen’s inner voice. The channelling vogue was popular, and very commercial, in America. Spangler’s version of the craze also opened the way for a subsequent fad of "channelling" Sathya Sai Baba, one of the guru influences at work in this same organisation from the 1980s onward.

In another direction, the "channelled" text known as A Course in Miracles (1976) achieved a following that staggered the critics. This became one of the influential books at the Findhorn Foundation. Helen Schucman claimed that her lengthy text was received via "inner dictation" from Jesus. The "transformation" genre is a switch-off to many critics.

Spangler’s exotic phrase Limitless Love and Truth (LLT) incorporated an influential theme associated with the Spiritualist Liebe Pugh (1888–1966). Peter Caddy enthused about this psychic and her network known as the “Universal Link.” Elsewhere, Pugh was considered credulous even by Psychic News (Sutcliffe 2003:87). Her habit of deference to numerous “spiritual” trends was not considered reliable. The Universal Link arose through visions claimed by Pugh and the businessman Richard Graves.

Graves elaborated upon his rather sensational experiences with a popular devotional painting of angels. A brilliant orange light emanated from this picture, and so on. The light was so strong that Graves received a burn. A Christ-like figure is said to have materialised, whom Graves called “the Master,” and whom Pugh called “Limitless Love.” Pugh even made a relief sculpture of this enigmatic figure in modelling clay. Psychic messages from “Limitless Love” were viewed as “prophecies of a new spiritual dispensation in which faculties of illumination and discernment would develop in the population at large, creating a ‘universal link’ in spiritual consciousness” (Sutcliffe 2003:88). In contrast, critics say that such beliefs contributed to a blockage in public discernment.

Peter Caddy wanted Pugh and her associates to join the Findhorn Community. His motives are suspect in that a wealthy benefactor was in the offing. Pugh died before there was any possibility of her moving to Findhorn. However, Caddy apparently gained her mailing list in a feat of new age strategy. “As a result, the Universal Link was effectively absorbed into Findhorn” (ibid:89). David Spangler evidently did not wish to be left out of the honours believed to be in process. Several years later, he did very briefly refer to the tendency for a cult to develop around Pugh (ibid). The main point to grasp is that the Findhorn Community entrenched itself, not through abstruse universal processes, but via mailing lists and the canny Caddy strategy of liaison demonstrated at Attingham Park. Plus the continual promotionalism cultivating the attention of a totally uncritical new age audience.

The LLT channelling of David Spangler identified the Findhorn Community as “one of several world centres in an emerging planetary network of ‘world servers’ – the term stems from the Arcane School’s ‘New Group of World Servers’ ” (Greenaway 2003:50). Critics refer to this as Alice Bailey optimism and Spangler lore. In 1973, Spangler returned to California to found another alternative community. The membership of the one he left behind is said to have quickly exceeded 200 (ibid). In Spangler’s wake came other servers or opportunists like William Bloom, who tilled the field of new age commerce in the 80s and 90s while exhibiting academic credentials and defying health warnings from Edinburgh University (Letter to BBC Radio).

Eileen Caddy tended to retreat from the new dominance of Spangler, whose contributions began to fill Findhorn News in 1971. In 1972, Eileen pronounced that she was to stop sharing her guidance with the community (Riddell 1991:80–1). Peter was evidently taken aback by this development. He had evidently become dependent on "guidance." He continued to rely upon “guidance” in the form of psychic messages from itinerant “clairvoyants” (Castro 1996:3). Peter’s psychology was not self-reliant; he continually needed reassurances. His estrangement from Eileen has been traced to the withdrawal of “guidance.”

In 1970, there were only about twenty members of the Findhorn Community. This number increased to over a hundred some two years later, a development attributed to the popularity of David Spangler with the younger recruits. In 1972, the community became officially known as the Findhorn Foundation. The simple caravan site developed into “The Park” with the aid of donations, loans, and charity status. Several books of Spangler were published during the 1970s by Findhorn Press. The influence of Sir George Trevelyan may be considered marginal by comparison with the overseas factor. In later years, Trevelyan sent a letter of protest to One Earth (the Foundation magazine) about the snub of Steiner expressed by a supporter of Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh. Trevelyan himself was considered an extremist in more sober quarters than the Wrekin Trust, whose policy was elsewhere considered to be reckless via undiscriminating tactics reminiscent of Esalen and the Findhorn Foundation.

5. Peter Caddy Exits and Eileen Caddy as Community Figurehead

Peter Caddy exited from the Findhorn Foundation in 1979. This event caused a shock. Many others left in his wake, leaving a very substantial hole in the community ranks. Eileen hoped that he would return, but this did not occur (save on brief visits). Some say that Peter Caddy left in pursuit of a fourth wife, Eileen now being a less enticing prospect. A partisan commentary states that Peter “left the community in 1979 to develop himself by means of a new series of relationships; he remarried in 1982” (Riddell 1991:84). This version dignifies the exit with a sense of significance. Eileen is presented as the heroine, conquering her shyness “to become a lecturer and spiritual guide, unafraid before mass audiences of thousands” (ibid:84).

Eileen did not become a therapist. However, the nature of her vocation is a subject for dispute elsewhere. She was afraid of incurring the displeasure of new managerial entities within the Findhorn Foundation. Her intermittent lectures served to buttress the commercial community which she did not appropriately tutor. Just as she retreated from Spangler, she also retreated from his successors, many of whom were far less inspiring.

Critics are sceptical of Carol Riddell’s glowing report above-cited. One reason being that Eileen was subject to an acute mood of retirement from the community until 1989, when she stated in a published article that she was no longer hiding after a recent event in which she was initially terrified of exposure before the community (Castro 1996:54). Eileen’s passivity, and general abstraction from the community, was a notable feature of the 1980s and after. The fact that she chose to endorse the commercial “Game of Transformation,” in her sense of changed role, is no particular reason to credit her discernment in saying “what I feel about the spiritual side of things” (ibid). The Game of Transformation is a lucrative board game.

Eileen’s “inner voice” became closely associated with the official Findhorn Foundation doctrine of “attunement,” extending to the practice in which participants seek their own inner guidance. The practice of “attunement” so frequently led to the facile assumption of spirituality being achieved. Spirituality was a coveted accomplishment in the Foundation cause of “planetary transformation.” Eileen Caddy became the mascot for what the managerial bodies described as “spiritual education.” A strong component of that drawback were numerous leaders of commercial “workshops” who taught the most facile and misleading concepts in too many instances.

During the 1970s, Cluny Hill Hotel was purchased by the community. The hotel was now a college of alternative therapy. American influences are impossible to ignore; the roles of “focaliser” and “facilitator” are an indication of ultimate origin. Other local properties were also acquired by the Findhorn Foundation, including Newbold House, which “adopted donation financing and is independent” (Riddell 1991:85). The caravan park was also acquired. “The Park” became the scenario of “global village” lore. Ecology was often mentioned, though rather loosely; the concept of sustainability was adopted in the late 1990s, often being sold in "workshops."

Both Maclean and Spangler had departed from the community in the early 1970s, leaving Eileen Caddy as the only remaining co-founder during the 80s and 90s (Spangler sometimes being counted as the fourth co-founder). David Spangler became noted for warning against drugs; however, his “channelling” vogue facilitated confusions in which intellectual talents were zero-rated. The Cluny Hill College of alternative therapy supposedly represented intuition. The relevance of critical faculties was denied. Learning skills were severely handicapped by the planetary transformation in which alternative therapy and pop-mysticism were considered holistic panaceas. This situation was effectively endorsed by the commercial programme brochures exalting the ubiquitous “Guidance” slogan of Eileen Caddy that commences: “Be at perfect peace; all is working out according to My plan.” The divine plan was inherent in the presumed “Guidance.”

The influence of David Spangler was celebrated in this community. He nevertheless departed for other prospects after only three years. The average length of residence for many inmates during the early 1970s is said to have been about six months (Riddell 1991:80). The urge to acquire properties caused a predictable financial plight arousing controversies. Economic problems were already surfacing in the late 1970s, to the tune of more than £400,000 (ibid:85). In 1983 the caravan park was purchased. At that period was completed the ambitious project known as the Universal Hall, which “contributed greatly, however, to a very large debt, and the collective energy of the community for construction was exhausted” (ibid:82). This impressive building proved expensive to maintain, while many community members were living in dilapidated caravans.

During the 1980s the membership was smaller, and inmates are said to have stayed longer. “Some independent businesses started to form” (Riddell 1991:89). Financial crisis was still looming in the late 1980s. Yet Riddell (writing at the end of the 80s) was optimistic about the future. “In 1988, Foundation members were involved in a long period of collective and individual attunement to create a new spiritual Core Group; this process represents the most determined attempt yet to move towards a spiritual democracy” (ibid:90). Was utopia just around the corner? Why did the new management team of the 1990s privatise the existing communal assets? Why were dissidents afflicted and outlawed? Why did the new executive leadership contrive higher incomes (for their own benefit) in a debt-ridden community?

Eileen Caddy remained a community figurehead for the rest of her life. She continued to live at The Park (the old caravan park). The fact is she did not lead the Findhorn Foundation; her low profile after Peter's exit tends to confirm her earlier reliance upon his organisational activities. The new management entities were all-powerful. Such matters have been subject to much confusion. The operative principles at work in the Foundation were frequently obscured by partisan exegesis. The “spiritual democracy” was a fantasy. Dissident reports serve to clarify what actually occurred behind the façade of divine guidance, spiritual education, and planetary transformation.

6. Esalen Influence and the Grof Phase

The community income did not come from gardening, but instead from “workshops” and related courses of purported spiritual education. Plus donations, which were strongly encouraged. Many American alternative trends were hosted at The Park and Cluny Hill College; these fads resembled aspects of the Esalen Institute very closely. New age celebrities like Caroline Myss and Arnold Mindell were favoured speakers, along with more native entities like Peter Russell and William Bloom. The high charges were aimed at an affluent international clientele broadly comprising the “new age” consumers. This trend culminated in the hosting of Stanislav Grof by Craig Gibsone, who was director of the Findhorn Foundation in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

l to r: Stanislav Grof, Craig Gibsone |

Until 1987, Grof was a psychedelic superstar of the Esalen Institute in California, a venue which supplied so many new age influences and assumptions. His subsequent career as a "Professor" of Psychology at the California Institute of Integral Studies has confused some assessors. That new age role did not reduce his entrepreneurial status in alternative therapy. This neo-Jungian businessman had launched Grof Transpersonal Training Inc. Grof continued his lucrative trademark therapy known as Holotropic Breathwork, which is audacious in the claims attaching.

Stanislav Grof is indelibly associated with Esalen, where therapy meant big business. "Spiritual transformation" was one of the lucrative phrases employed in the consumer ideology. Very suspiciously, criticism was frowned upon as being judgmental, a taboo drawback supposedly indicating Neanderthal characteristics. The Findhorn Foundation assimilated a great deal of the Esalen attitude. Gibsone was the vehicle of uncritical sponsorship for Grof commerce. Gibsone became a workshop practitioner of Holotropic Breathwork, meaning hyperventilation for a client fee.

The Grof phase (1989–93) at Findhorn met with setbacks. The Foundation management simply deleted relevant details from their records, a characteristic of their strategy. Holotropic Breathwork gained internal resistance, although Gibsone acquired many supporters. Dissident reports were shunned as being judgmental. Confusions about Grof’s “therapy” continued at the Foundation for years after, despite official intervention from the Scottish Charities Office. See further Letters to the Office of the Scottish Charity Regulator.

7. The 1990s and Economic Problems

Peter Caddy remained a voluntary exile from the Findhorn Foundation. He died in 1994 in a car crash in Germany. That was after his fifth marriage, Eileen having been his third wife. For his version of events, see P. Caddy, In Perfect Timing: Memoirs of a Man for the New Millennium (1996). Caddy’s high estimation of his role is not universally agreed upon.

Eileen’s autobiography Flight into Freedom (1988) was awarded canonical status. Eileen became celebrated on British television, in a very abridged manner. Many outsiders received the impression that she was the basic guiding factor in the community she had helped to create. In actual fact, a fair number of other individuals, far less well known, were the operative conductors of management decision and public relations. One of these was strongly associated with Sathya Sai Baba, while another became a convert to Grof doctrines and temporarily succeeded in imposing Grof’s Holotropic Breathwork upon the partially unwilling community.

l to r: Dorothy Maclean, Eileen Caddy; Kate Thomas at Findhorn, 1988

The Times online obituary (for Eileen Caddy) does not provide an in-depth assessment; the reporter probably lacked many of the available details. Instead, a very skeletal description of the 1990s phase is proffered. The obituary observes that the Findhorn Foundation was threatened by bankruptcy, and "also investigated by the watchdog Scottish Charities Office.” That is correct, but no further details are given, so the blank is extensive, to say the least. “The community responded by creating a management structure and a multitude of outreach programmes.” This is very far indeed from being the comprehensive truth.

The Times obituary was clearly attempting to follow the orthodox version preferred by Foundation spokesmen, who have been assessed by critics as media manipulators. One discrepancy is that the management structure exacerbated the substantial economic debt which arose; this problem was concealed from view for a surprising number of years, until 2001 in actual fact. Prior to that date, one management team had been obliged to resign in failure, the internal contradictions of their policy being too much even for the Foundation staff to accept. The internal problems were further covered up to general view by the new management team, who ensured that the community emerged unscathed from controversy by emphasising their NGO status, acquired in 1997, while suppressing details of the economic malady. NGO status does not necessarily decode to perfection, especially if that status is acquired in circumstances of evasion concerning basic details.

The Times obituary asserts that Eileen Caddy joined the management committee after worrying that the Findhorn Foundation was becoming too commercial. This does not tally with dissident and critical reports, which utilise more detailed data (some of which can be found on this website). In reality, Eileen assisted the commercial trend by remaining a puppet of the management teams. In 1994 she expressed the endorsement: “When all of us can think in millions of pounds, we will draw millions of pounds to us” (Shepherd, Letter of Complaint to David Lorimer, 2005, booklet version, p. 16, citing Castro 1996:190). This statement was not a private disclosure, being inserted into an influential circular letter to the community. That letter was both a public and “open community” circular seeking donations after the death of Peter Caddy in February 1994.

The demise of the co-founder was treated as an opportunity for a major fundraising operation by the Foundation director Judy (Buhler-)McAllister. The Forres Gazette reported that the circular was being sent out to eleven thousand “regular customers” of Foundation courses (and workshops). Those clients were located in America, Europe, and Britain. A copy of Peter Caddy’s obituary was enclosed along with a donation form. Plus the persuasive letter from Eileen Caddy addressed to “My dear family,” which included her eccentric (and inaccurate) interpretation of the word Findhorn as meaning the “Horn of Plenty.” The explicit nature of that letter, as a goad to donations, was unmistakable; the reference to millions of pounds sterling clearly denoted the objective (Castro 1995:189–90).

8. The Real Situation of Eileen Caddy

In her "My dear family" letter, Eileen refrained from mentioning significant matters which she had disclosed in private. Her confidante had been Kate Thomas, a relative newcomer to the Foundation who had chosen to live in Forres. Eileen had invited Thomas to her new home at The Park; the host seemed in desperate need of discussing internal matters relating to her organisation. She prefaced a major disclosure by swearing Thomas to strict confidence, stressing that the information she gave could be damaging to the community reputation. It was obvious that she dared not talk to various other women, who were orthodox supporters believing in the spiritual nature of the community role.

Eileen disclosed to Kate Thomas that the managerial figures of the Foundation had ceased to take her advice. Further, the persons concerned were themselves worried that their diverging attitude towards her would become known. They had been influenced by Peter Caddy’s departure and critical attitude towards herself. On this point, Eileen lamented that Peter had told her, by telephone, that he no longer believed in any of her guidance. She had also received a dismissive letter from Peter reiterating this outlook, one which made clear that he now considered she had been deluded from the start. Eileen was very upset by that recent letter, which was never made public knowledge.

Eileen repeatedly invited Kate Thomas to her home at The Park. She also commenced a telephone contact with this new friend. Eileen was very troubled by such factors as Craig Gibsone (the Australian director of the Foundation) being immune to her advice and complaints. Gibsone, a long term inmate of the community, had noticeably sought ideological support in Tantric Buddhism, which he often mentioned. His conversion to Holotropic Breathwork accentuated the fact of his acute tangent from the Caddy guidance.

There was no effective leadership within the Foundation, influential staff tending to do what they wanted, with some frictions developing. Eileen felt that things had got out of control. Kate insisted that Eileen should alter her tactics and stand firm against the problems, which would otherwise get worse. Eileen knew that this was good advice, which she proved incapable of following. She continually demonstrated that she could not stand up to assertive personalities, especially certain men within Foundation ranks who were known to be difficult.

Two of these overbearing officials became aggressive towards Thomas. There was nobody to stop them. Eileen was terrified of saying a word against Eric Franciscus and Loren Stewart. She simply kept quiet and stayed well in the background. She did not even want to know about the events concerning them. This grim situation involved the persecution of a younger friend of Thomas, who had joined the community only to become the victim of authority complexes. These and other problems caused Kate Thomas to compose a chapter in her autobiography describing flaws in Findhorn Foundation events. That chapter included critical references to Eileen’s teaching, which had set the tone for some basic attitudes in the community, tending to mesh with simplistic therapy emphases derived from elsewhere.

After the publication of The Destiny Challenge in May 1992, Eileen remained in contact with Kate Thomas. Surprisingly, she did not read the Thomas book, though she became acquainted with the basic contents of chapter 14. Thomas discovered that Eileen was not a studious type, reading only the short and popular “new age” works favoured within the Foundation. Eioleen Caddy wanted to be friends with Thomas, providing that she was not expected to stand out against the problem entities. She did not want to forfeit in any way her new home at The Park. She frequently spoke of her children rather than anything else. Thomas despaired of obtaining a due response from her. See Disappointment with Eileen Caddy.

Eileen demonstrated her evasive tendency to the full in an episode briefly recorded by Thomas (in an understatement). The female victim of staff hostility made a desperate visit to Eileen’s new home, asking the occupant why she “had done nothing at any step to correct this situation” (Thomas 1992:975). Eileen listened to the anguished report of her visitor, but gave no explanation. Instead, the visitor was told that “if she was unhappy, she should leave” (ibid:976).

9. Conflict Resolution a Farce

The abused visitor left Eileen's home in despair, being “in a state bordering on collapse” (Thomas 1992:976) when she afterwards telephoned Kate Thomas. The latter immediately contacted a retired medical practitioner in Forres, who promptly went by car to the distressed woman. The state of this woman was such that the doctor took the sufferer back to her (the doctor’s) own home. The sufferer soon afterwards relinquished membership of the Foundation.

That episode occurred in 1991. As the present writer was a personal acquaintance of the medical practitioner mentioned, I can here fill in some details. Dr. Sylvia Darke (d.1999) was a retired English G.P. who had settled in Scotland after a distinguished career; she had been connected with the Ministry of Health, also acting as a consultant to the World Health Organisation. In her later years she took a liberal attitude to some of the more restrained “new age” ideas, but firmly drew the line with regard to the Findhorn Foundation. She lived in Forres, but refused to join the Foundation, regarding that organisation with considerable scepticism. She made a few visits as an observer, proving very suspicious of the casual attitudes and therapy jargon that were prevalent. Her opinion of Eileen Caddy was very low, plummeting to zero when she rescued the unfortunate woman abovementioned from a very stressed predicament. The medic concluded that the sufferer had been victimised in an unmonitored situation of grave implications.

l to r: Judy McAllister, Sylvia Darke |

The sufferer quickly recovered under Dr. Darke’s supervision. She nevertheless had to leave the Foundation in the interests of her health. Dr. Darke’s assessment of the Foundation remained very critical thereafter, an outlook converging with that of other medics in Forres. The medic wrote some complaining letters to the local newspaper about subsequent events. In 1994, Dr. Darke made a special visit to the Foundation director Judy Buhler-McAllister (later known as Judy McAllister). Dr. Darke intended to discuss pressing discrepancies in the Foundation policy currently being enforced by the director. The Canadian director refused to see the senior British medic, who had to wait outside in her car before driving away. Judy McAllister refused permission for the senior medic to enter the building in which her managerial office was located at The Park (Shepherd 2005:215).

Judy McAllister was also censorious in relation to Kate Thomas, whom she suppressed for years, refusing pleas for a fair hearing, which was never granted. This situation included dead end telephone conversations of the victim with the unyielding Judy McAllister, whose despotic sense of power refused a meeting with Thomas, also prohibiting any other concessions to such a close neighbour. Incidentally, I chanced to overhear one of these conversations on an interior extension line at my mother's home in Forres. McAllister expressed a continual put-down, purportedly representing spiritual education, no criticism of which was tolerated.

This situation was rendered even more discrepant when McAllister took a prominent role in "conflict resolution workshops" at the Foundation. These events were commercially successful but totally unconvincing to informed parties. Judy McAllister was also prominent in the Game of Transformation (the Transformation Game), a board game elevated to very dubious status. Like conflict resolution, this is simply a game, though played as a moneyspinner. McAllister acted for years as a facilitator (trainer) in the Game, in a course for which the charge was £1850, a speciality fee advertised by the Findhorn Foundation College (formerly Cluny Hill College).

In 1994, Eileen Caddy betrayed her conscience by siding totally with the domineering management (and the director Judy McAllister) against Kate Thomas, apparently under strong persuasion. See Part Two below. Despite this lamentable example, Kate never divulged the matters which Eileen had disclosed in confidence. In the late 1990s, Thomas had further contact with the co-founder, though of a more incidental nature than formerly. Eileen did not refer to the past, for the most part expressing only mundane interests. She never wished to discuss the management, whom she had chosen to support despite her dislike of many policies they furthered. Eileen once visited the home of Thomas, which she knew well, this having formerly been a Foundation support venue, one where Eileen had a small upstairs room reserved for her use.

Kate Thomas passed on details from Eileen to only three people – myself, Stephen Castro, and Dr. Darke. This was in strict confidence, which all observed. Stephen Castro refrained from mentioning the upsetting details about Peter Caddy in his book Hypocrisy and Dissent within the Findhorn Foundation (1996), though he had good cause to do so. Thomas did not want the details to be disclosed while Eileen was still alive. In view of long term attitudes of the Findhorn Foundation, such as their internet stigma of Castro and Thomas (see Part Four below), relevant details have been supplied here in the interests of historical reporting.

Dr. Darke was one of those local residents who felt strongly about the promotion of Holotropic Breathwork by Craig Gibsone and his associates. Reports about unpleasant aftermath symptoms of this presumed therapy became widespread in Forres. An international promotion campaign by Grof and his supporters misled many subscribers. Women were more often the sufferers in this direction, though some males also encountered serious problems, including nervous breakdown.

Eventually Dr. Darke wrote a strong letter of complaint to the Scottish Charities Office, serving to complement communications from other objectors to that Office (the SCO failed to act in relation to additional matters of which they were apprised). The Breathwork was only one of the more obvious drawbacks within the indulgent community lacking any effective leader. Other "therapies" also caused problems and confusions, while “spiritual counselling” was a popular trend in which many doubtful experts gave advice on what to do. “Letting go” was one of the panaceas accompanying the facile slogan “Be here Now.”

The sceptical Dr. Darke became concerned about what Eric Franciscus was doing, having had to monitor his victim abovementioned in 1991. She felt extremely perturbed that Franciscus was the official in charge of “Education” at Cluny Hill College (subsequently renamed Findhorn Foundation College). While not a Breathwork practitioner, he was considered an expert on therapy and counselling. Those activities were largely what was meant by the word “Education.” Franciscus and his wife also conducted regular and commercial “spiritual pilgrimages” to India. Eric Franciscus became strongly associated with the “miracle guru” Sathya Sai Baba of Puttaparthi. He and his wife subsequently became members of the management team benefiting from the acquisition of NGO status which baffled locals.

Dr. Darke expressed the conclusion that a principled standpoint, such as that demonstrated by Kate Thomas, opposing the follies promoted by Foundation officials, was crucially necessary for public health. This medic's view of Holotropic Breathwork (hyperventilation) was scathing; she learned much about local victims. The workshop theme of "conflict resolution" was a farce. Further, in her assessment, the Transformation Game amounted to a diversionary commercial pastime sold by persons who jettisoned scruple. She reiterated:

When a medical doctor requests an interview, on grounds of known abuses, and is not permitted even a moment, then you know that the situation is seriously wrong.

10. Peter Caddy Endorses a Dissident Book

An irony is that Peter Caddy can be numbered amongst the supporters of Kate Thomas. Less than a year before his death, in March 1993 he sent Thomas a letter which stated: “Many of your expressed concerns about the so-called New Age movement and particularly the Foundation, will, I trust, receive the attention they deserve” (Castro 1996:189). This was his cordial response to The Destiny Challenge (1992), which contains a lengthy chapter on the Foundation. Perhaps his conversion to Hinduism had made Peter Caddy more critical of his earlier role and Eileen’s guidance. Be that as it may, a co-founder of the Findhorn Foundation endorsed the heretical book suppressed by the management. This gesture was in strong contrast to Eileen’s fear of authority, which caused her to side with the suppression and deny her former friend and confidante any democratic hearing.

11. Pierre Weil, NGO Status, and Peace Anomaly

The Times obituary for Eileen Caddy represents a surface layer in reporting the Caddy events. This commemoration informs that Eileen told an interviewer, in 1999, that she regarded herself as the “spiritual anchor” of the management committee (or team). The management teams of the 1990s were content to depict Eileen as their spiritual figurehead, a theme which had become part of their mythology. This gesture is not sufficient to explain how they gained NGO status associated with the UN Department of Public Information.

Pierre Weil |

Close analysts concluded that NGO status was secured via the Foundation patron Pierre Weil (1924-2008), in a procedure that remained obscure. Dr. Weil spent most of his time in Brazil at the Holistic University he founded. This alternative university at Brasilia emphasised peace. In relation to new age conceptualism, that institution has been accused of employing a vague and uncritical approach. Weil was an author and "workshop" innovator.

Dr. Weil was committed to the ideal of world peace, while completely ignoring the discrepant factor of suppressed close neighbours in Forres. One of these suffered manic discrimination on the occasion of a Weil "living in peace" workshop dating to May 1993, occurring at Cluny Hill College. Kate Thomas (Jean Shepherd) lived very close to Cluny Hill College, in a house formerly used by the Foundation (as her son, I lived in the same house for seven years and have vivid memories of the period). Weil also ignored the medical warnings about Holotropic Breathwork, an activity which he endorsed in Brazil, to the gratification of practitioner Craig Gibsone.

A UNESCO advisory of 2002 bore the title of Conflict Resolution and "The Art of Living in Peace." This deferred to Weil's peace method "that takes account of all a person's psychological, emotional and physical characteristics, so that learning about peace can be internalised." Unfortunately, this diagnosis had been proven wrong at the Findhorn Foundation, where negative emotion was permitted to achieve an act of suppression. This occurrence is the more lamentable in view of the acute tendency to suppress all such details of dissident events. The episode was recorded in a book ignored by the Foundation, whose sense of history is extremely deficient. Cf. Castro 1996:110. Further, UNESCO failed to reply to a pointed complaint in relation to such events. See section 30 below and Letter to UNESCO.

PART TWO: DISSIDENT KATE THOMAS AND EILEEN CADDY

Kate Thomas (1928-2017) was both the confidante and critic of Eileen Caddy, gaining an intimate knowledge of the latter’s psychology. Likewise British, she was a nearby resident of Forres who conversed with Eileen on many occasions until 1993 (and sometimes in the latter’s home at The Park by invitation). Thomas demonstrated a scruple that was acknowledged and admired even by one of the opposing practitioners of Holotropic Breathwork. Caddy wavered between a feeling of kinship with Thomas and a feeling of deep fear about upsetting the management. The fear complex proved victorious.

Thomas discovered that Eileen Caddy was socially amenable, but very evasive on points of community wellbeing. Caddy admitted to Thomas that she did not agree with various trends promoted by the management. She also gave lame excuses for her inertia in failing to confront management tactics. Eileen Caddy divulged that when she had formerly complained, the management had ignored her. Caddy’s policy had become one of taking the line of least resistance, which meant no resistance at all. That was how the 1980s closed and the 1990s commenced.

Kate Thomas, Cambridge 1978

The discussions between Caddy and Thomas were very unsatisfactory, the former becoming apprehensive at being drawn into possible frictions. Caddy demonstrated a singular failing in relation to Stanislav Grof’s controversial Holotropic Breathwork, a trademark therapy which worried many people in the Findhorn Foundation community (to such an extent that a number of them departed from the scene in a perturbed state of mind).

12. Crises of Holotropic Breathwork

Eileen Caddy’s nominal protégé Craig Gibsone was the principal instigator of Holotropic Breathwork workshops. She had contracted a habit of never interfering with this man, who was resistant to correction.

One of the younger recruits at the time of Spangler’s sojourn, Gibsone had since strongly entrenched his claim to community salience. Caddy herself did not agree with the doctrines of Grof, and was not a therapist. In contrast, Gibsone was totally uncritical about Grof theory and commercial practice, himself becoming a "workshop" star in that context.

A recorded interchange, between Thomas and Caddy in 1990, concerned Holotropic Breathwork. Caddy here agreed with the concern of Thomas about the Grof “therapy.” However, Eileen’s attitude was pronouncedly evasive. Thomas referred to the recently observed drawbacks in Holotropic Breathwork sessions at the Foundation, commenting that some participants “could become seriously deranged, or even die.” The response from Caddy alarmed her. “Perhaps that is what must happen to make them pay heed,” said Eileen, who now divulged that Gibsone had opposed her own critical reflection upon the Breathwork. Eileen had then docilely retreated from the issue.

Yet as a consequence of talking with Kate Thomas, Eileen said that she would approach the guest American facilitator (a pupil of Grof) in charge of Holotropic Breathwork proceedings (being a tutor of the recently converted Gibsone). Eileen later told Kate Thomas that this facilitator, together with Gibsone, had agreed to provide a support group for those who might need “spiritual emergency” treatment. Emergencies were recognised to occur, but interpreted in a Grofian “spiritual” manner very different from medical assessments (all considered to be outdated by Grof and his supporters).

Thomas was still alarmed, because Caddy would make no public statement, remaining totally anonymous in her objection. Other Foundation people expressed disbelief when Thomas told them that Eileen had made some intervention, as they had no idea that Eileen was opposed to the Breathwork (Thomas 1992:935–6). Such persons merely assumed that Thomas was exaggerating. This grave failure of Eileen Caddy, to register a complaint in public, was disastrous for the train of events.

Gibsone retained full play in his ambitions to be a practitioner of the controversial therapy. Subsequent support groups transpired to be a necessity for distraught women, some with revived memories of sexual abuse. The problems were covered up, as usual. Gibsone proceeded in his plan to make the Foundation a worldwide training centre for Holotropic Breathwork. Over three years elapsed before official intervention stopped the tide of casualties. While some Breathwork participants became euphoric, others suffered greatly, and sometimes with damage. The details were cast into oblivion by the Findhorn Foundation hierarchy.

13. Toeing the Party Line of Suppression

In a comment about Eileen Caddy’s teaching, Thomas distilled: “Eileen teaches that one is already a Christ-filled being and that affirmations of this condition are all that is necessary for interior development. One should ‘love oneself’ with all one’s faults and accept oneself just as one is. Self-examination is not a requirement, and the correction of flaws is never mentioned” (Thomas 1992:912–13.). That describes so much of what occurred in the indulgent community known as the Findhorn Foundation.

A friend of Thomas was Stephen Castro, who produced a significant account of discrepancies within the Findhorn Foundation. He also encountered Eileen and was very sceptical of her belief system, although he did not openly express this. In a letter to the present writer dated April 1st, 2007, Castro stated:

The ‘inner voice’ heard by ‘Elixir’ (Eileen Caddy) in the formative early years really was believed to be God.… When Craig Gibsone put her name forward on a community bulletin board, indicating she was going to be among the participants in the original programme for Holotropic Breathwork (thus endorsing the programme), she quickly asked for her name to be removed after learning what he had done. Her ‘inner voice’ said it was not for her. The ‘inner voice’ being of course a convenient screen to hide behind so that one need never have to stand up and be counted by speaking from the first person, i.e., oneself.

Eileen Caddy toed the party line. She required a goad from Kate Thomas even to express a secretive complaint that produced a support group for Holotropic Breathwork. Her reputed “inner voice” of the 1960s now amounted to a bystander endorsement of dubious policies from which she herself felt largely estranged. Such realistic details were foreign to management policy, which was careful to suppress The Destiny Challenge (by Thomas) in a memorable manner. The detailed report of Castro in Hypocrisy and Dissent was likewise eschewed. The unwelcome reporting continued in my own Pointed Observations (2005, Part Five). These sources have all been suppressed and ignored by the Foundation management strategy, a fate also befalling critical accounts by other writers (e.g., J. P. Greenaway, In the Shadow of the New Age, 2003; C. Coates, 21st Century Theosophy, 2005).

An online account by Kate Thomas includes an update on the Caddy problem, further aggravated by the Findhorn Foundation College (the new commercial version of the therapy venue Cluny Hill College, promoting the drawback known as Holistic Learning, which has encompassed the myth of “conflict resolution” and the Transformation Game). See SMN Events 2000–2004, chapters 1 and 5.

In the spring of 1992 appeared the book by Kate Thomas entitled The Destiny Challenge. In the lengthy chapter fourteen, she describes her contact with the Findhorn Foundation from 1988 onwards, and how she objected to Grof’s commercial Holotropic Breathwork and other drawbacks. Craig Gibsone effectively screened her out of any chance of a democratic hearing. This strategy was backed up by two ruthless Foundation personnel who victimised her for daring to criticise internal policies. These two men ensured that her membership was severely restricted and annulled. These two Findhorn Foundation oppressors were a German and an American respectively, the former being more relentless and also gravely victimising a female friend of Thomas who had joined the Foundation.

When the Foundation staff acquired a copy of the Thomas book, they reacted to the content of chapter 14 by attempting to impose a legal interdict. One of them publicly denied in a local newspaper that Thomas had ever been a member of the Findhorn Foundation. That was a big mistake of Alex Walker. The resultant press exposure of Foundation problems electrified a local audience, to such an extent that photocopies of chapter 14 were passed to interested parties such as medical doctors.

Kate Thomas proved willing to reconciliate, herself initiating this move. Yet once again, the proud and vindictive staff of the Findhorn Foundation asserted their primacy. There could be no reconciliation for them, the commercial promoters of conflict resolution (often appearing in the American rendition of conflict facilitation, studiously employed by Foundation promotionalists to gain a wider audience). They proved many times over what their orientation really amounted to. Some of them were in trouble when the management team crashed at the time of gaining NGO status. Others crept past that fiasco to gain glorification as inheritors of the United Nations mantle.

While the ill-fated management team was scheming how to siphon off funds for their new salary increases initiated by Gibsone, a very revealing event occurred in 1994, revolving around Eileen Caddy. The management team was the actual instigator of the tactic involved. The docile Caddy was here the condoning witness to a management policy of total suppression of Thomas in the wake of her commendable gesture of reconciliation. Kate Thomas was the only one who forgave, while the other participants harboured animosity and vengeful pride. The management, having already blocked her former membership of the Foundation, now also ruthlesssly excluded Thomas from Open Community membership, so that she could have no say in community events or conduct any defence of her own acutely misrepresented position. She was stifled while being slandered. See Kate Thomas and the Findhorn Foundation. This was new age "conflict resolution."

The aberrant situation deeply shocked some onlookers (including myself), who recognised that the Findhorn Foundation were reversing their declared priorities in such trite lip service themes as unconditional love. Democracy was, and is, a myth in new age planetary transformation. The "Vatican of the New Age" (a media tag for the the Findhorn Foundation) may be compared with a medieval prototype (or archetype) of elite exclusionism.

14. Unconditional Love and the Testimony of Howard Whiteson

When Howard Whiteson intervened on behalf of Kate Thomas, he could not elicit a grain of sympathetic response from Eileen Caddy about the dissident situation. His encounters with prominent Foundation officials further served to totally alienate him (Castro 1996:138ff). This was one of the episodes in Castro's book which the Foundation management were subsequently very keen to suppress.

|

Howard Whiteson had hoped to join the Foundation, but the setback caused him to leave the vicinity in revulsion. He never returned, remaining averse to the Findhorn Foundation. The “inner voice” of Foundation “attunement” decoded to authoritarian abuse of basic rights of representation and issues relating to communal wellbeing. Whiteson moved back in despair to England; without actually meaning to do so, he also lost contact with Thomas. Many years later, in 2006, he resumed contact with Thomas (via correspondence) and contributed an account of his former contact with Eileen Caddy. This is reproduced here:

When I returned to the Findhorn Foundation in 1994 for a second visit, I was shocked to learn that Kate Thomas had been expelled from membership, and in an arbitrary and undemocratic manner. I had first met Kate in Cambridge during the 1980s, and found her to be a woman of remarkable probity, honesty, and insight. I found various Foundation people busy denouncing Kate, but none of them actually seemed to know what she was reputed to have done wrong.

Despite much rumour-mongering by the Foundation staff, the fact was that Kate’s case had never been heard in an open forum. Of course, such a platform would have allowed her an opportunity to defend herself, as well as to publicly reveal the nature of the treatment she had received at the hands of Findhorn Foundation figureheads, who had much vested interests in ensuring her continued silence. During my stay, I made every effort to gain Kate a due hearing, but my letters, phone calls, and personal discussions with members and trustees only ever met with a wall of indifference verging on callousness, and at times, downright hostility.

Such stonewalling tactics are characteristic of cults, another being the pervasive use of jargon. The latter tendency was rife amongst Foundation members, many of whom referred to themselves as "Christ-filled." The connotations of this phrase remained difficult for me to fathom. Some members referred to "finding the God within," a particularly abstract concept. When questioned, one member told me he was "divinely ordinary," that although everything he did was ordinary, he imbued it with divinity. I found this stance hypocritical, given the attitude shown towards Kate. But who originated the quixotic terminology? In her autobiography, Foundation co-founder Eileen Caddy referred to herself as "a beautiful Christ-filled being" (Caddy, Flight Into Freedom, London: Element Books, 1988, p. 207). Had this and other self-aggrandizing affirmations convinced Foundation members that Caddy was in receipt of cosmic "guidance" which ensured that the Foundation would pursue a correct course of spiritual development?

The truth was rather more mundane. On one occasion, Caddy "had no guidance to write down. Although I felt a hypocrite, I pretended to hear something then wrote down the first thing that came into my head." Despite this inauspicious tactic, Caddy’s guidance went on to inform her: "You are Mary, the mother of Jesus the Christ" (ibid., p. 118). Being "Christ-filled" took on new significance.

Perhaps in the role of "divine mother," Caddy asserted: "Gromyko from Russia and George Shultz of the United States were meeting to discuss a possible halt to the arms race, so I visualised the Christ within those two world representatives. I saw them transformed, their faces filled with joy and happiness and I saw them taking this change of consciousness back to their respective countries. In my mind the destructive energies changed to positive, constructive ones, and a wonderful healing joy of the earth took place, filling it with light, love and joy" (ibid., p. 223). The Greenham Common women, who held permanent vigil outside Britain’s nuclear arms HQ, would have been dismayed to learn that years of political protest had not led to nuclear disarmament. Instead, "Christ-filled" Caddy had purified the planet with her loving, joy-filled mind.

Another clue to Caddy’s psychology lay in a catchphrase she frequently employed, and which Foundation members just as frequently repeated: that in all their actions they were practising "unconditional love." No one I met within the Foundation precincts ever questioned whether love could actually be unconditional. More objective New Age analysts, however, were not so easily persuaded: "to want to give or receive unconditional love is to place a condition on love – namely, that it have no conditions. This is not just a play on words. Abstractions by their very nature leave out the living context, and when dealing with emotions, this is particularly treacherous. If the abstraction omits or denigrates important aspects of the living situation, strange and often harmful consequences and distortions result." (Kramer, J. and Alstad, D., The Guru Papers: Masks of Authoritarian Power, California: Frog Ltd., 1993, p. 265)

Harmful indeed were the unconditional distortions Kate Thomas received in a living context of persecution. Despite such glaring anomalies, which were carefully kept from the tender ears of newcomers, the promise of unconditional love greatly influenced visitors. They willingly forked out large sums of money to hug each other, open up, and narrate intimate life events (often traumatic or abusive) during frequent and lengthy group "sharings." As I saw it, the resultant tide of intense emotionality short-circuited their ability to reason. This may have contributed to the difficulty I had conducting any form of coherent discourse with New Age adherents. In fact, many participants seemed to have undergone the conversion syndrome known as "snapping," after which they became followers who routinely fell in with the party line. (See Conway, F., and Siegelman, J., Snapping: America’s Epidemic of Sudden Personality Change, Philadelphia and New York: J. B. Lippincott, 1978)

If Caddy was a planetary healer, then one might imagine her as some sort of divinely-inspired saint. When I met her, she cut a singularly uninspiring figure. I requested a moment of her time, to which her immediate response was to bark a brusque, "No." A little later, I gained a brief hearing, whereupon she announced that in Kate’s case, democratic processes were unnecessary, as the organisation was being watched over by God. Furthermore, Caddy opined, Kate had been expelled for the horrendous sin of "writing a book."

Perhaps the crux here is that a woman who fantasised herself as Mary was not so much "Christ-filled" as "ego-filled." Instead of divine behaviour, "Christ-filled" members exhibited demonic misbehaviour towards Kate Thomas. I will never forget the rage which manifested from such Foundation stalwarts as Charles Peterson (focaliser of Cluny), or Loren Stewart (member of Management Group). Once their hugging, smiling, and sotto voce affirmations ceased, something altogether more malevolent emerged. It was Kate’s misfortune to be at the receiving end of their aggression. Sadly, collective New Age acrimony was still in evidence as recently as 2001, when Kate was seventy-two years old (Shepherd, Pointed Observations, 2005, pp. 180–3). Participation in too many Findhorn Foundation workshops, it seemed, resulted in a form of unconditional hatred.

In the end, the tragedy remained that Kate was prevented from contributing effectively towards Foundation life. Eileen Caddy and the community of "unconditional love" remained the unrelenting barrier until Eileen’s recent death in 2006.

Eileen Caddy was now a screen against relevant criticism, her position effectively condoning the motivations underlying an attempted legal interdict on The Destiny Challenge. The Foundation solicitor was unable to give the Foundation staff any license; people could not be stopped from criticising what was potentially hazardous or events which seemed unfair.

Publication of The Destiny Challenge had not prevented Caddy from being in contact with Thomas during 1992–3. She actually agreed with some of the complaints made by Thomas in chapter 14, though being averse to any criticism of herself. Eileen’s conversation with Whiteson was clearly influenced by the management, reflecting several of their idioms – such as Thomas being a “nuisance,” and that she wanted to “take over the Foundation” (Castro 1996:151). A variant of this distortion, though not used by Eileen, was that Thomas wanted to “save” the Foundation, an accusation which gravely misrepresented objections to the traumas and dysfunctions caused by Holotropic Breathwork.

The justifiable complaint made by Kate Thomas against Holotropic Breathwork had been suppressed, despite that complaint having been totally vindicated by medical scruple and SCO recommendation. The SCO (Scottish Charities Office) had recommended (to the Foundation) against the commercial Grof therapy the previous year (1993), after the report submitted by the Forensic Medicine Unit at Edinburgh University. Eileen Caddy chose to ignore such factors, her fear of management displeasure being a major psychological complex in her case. She allowed the management to decisively eliminate the major objector to Holotropic Breathwork, while spokesmen like Alex Walker were attempting to justify the role of Grof therapy in Foundation precincts.

The Breathwork continued to be practised privately at the Foundation, in defiance of the official recommendation and medical warning. The danger technique was afterwards spread with even greater defiance in England by such new age activists as William Bloom, who had become a prominent “workshop” celebrity at the Findhorn Foundation (Letter to BBC Radio). The BBC supported Bloom in a new age mood of unreasoning compliance; they declined to make any criticism of his behaviour, and continued to support the mythical role of the Foundation. Women were in particular danger of discomfort from Grof therapy, as a medic had discovered.

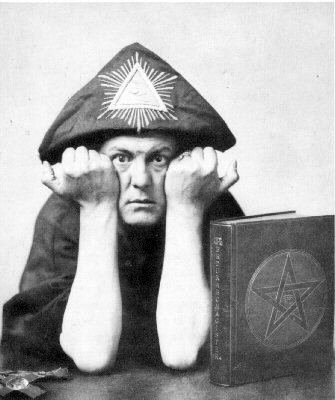

Thomas had also warned, in her chapter 14, against such controversial matters as neoReichian therapy, and the influence of Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh and Aleister Crowley – the books and accessories of both these new age icons were sold without scruple in the Foundation bookshop. Eileen Caddy turned a blind eye to the inappropriate commercial policy. Apparently all that mattered to her was for “Eileen’s Guidance” to be continually emphasised in Foundation literature. Visitors were familiar with her “inner voice” statement:

Be at perfect peace; all is working out according to My plan.

The Rajneeshi terrorism in Oregon, occurring in the 1980s, was effectively justified by the Caddy Guidance plan. Nobody in the Foundation bothered to chart the divisions between socially beneficial and socially harmful behaviour. The divine plan of Caddy Guidance did not envisage criticism of anomalies and drawbacks. The Foundation management and Eileen Caddy represented the Door to Heaven, while critics represented the Door to Hell.

PART THREE: COMMERCIAL EXPANSION AND MISMANAGEMENT

The door to commercial superficiality was opened by this organisation, notorious in some quarters for the Transformation Game, which has figured extensively in their promotional brochures for many years. The Online Store of the Findhorn Foundation has sold “Angel Cards” (price £6.95) in the context of a new age supermarket invitation to sample, e.g., books, cards and calendars, and “Tools for Transformation.” The ad appeared in the Courses and Workshops brochure, noted for the high prices charged in the workshop calendar. In this ad, transformation explicitly covers the Transformation Game and Oracle and Card Sets (Findhorn Foundation Courses and Workshops May-October 2004, p. 34).

The Transformation Game is a novelty selling for extortionate prices in so-called workshops, while oracular accessories were another regular distraction in this exploitive milieu. The pitch is even more obnoxious when sanctioned by the divine plan of Caddy Guidance. Despite warnings, UNITAR (United Nations Institute for Training and Research) blindly decided to boost the Foundation profile as a CIFAL centre in 2006, an arrangement ending in 2018. UNITAR bureacracy blocked due criticism of the Foundation for twelve years.