Philosophy, Richard Tarnas, and Postmodernism

Richard Tarnas |

CONTENTS KEY

2. Richard Tarnas and the Passion

4. Official Death of Metaphysics

8. Jung and Pseudo-Metaphysics

10. Negotiating Contractions in Academe

11. Avoiding a Neo-Jungian Hazard

12. Findhorn Foundation Holistic Censorship

Many entries on this website comprise critical treatments of alternative or "new age" thought. That form of thinking first arose in America during the 1960s, though speedily being transplanted to other countries, including Britain. There was an obsessive anti-establishment mood, emphasising new cliches such as "higher states of consciousness." The advocates of this alternativism saw themselves as pioneers of a new world era; peace and love were widely proclaimed to be characteristic traits of the innovation.

Much of the enthusiasm was inspired by users of cannabis and LSD. The extremist academics Timothy Leary and Richard Alpert created a bizarre lore about expanding consciousness; these psychedelic enthusiasts were influential in the popular vogue for Oriental religions. Their version did not impress many scholars of Buddhism and Hinduism (including Vedanta). Meanwhile, the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi achieved an opportunist celebration of Transcendental Meditation, a bestselling novelty which claimed the Beatles as some of the fans. Such trends had a transient aspect, leaving many disillusioned persons wondering what was really happening.

Many gurus benefited from the new mood of alternativism. At first they were all treated as renaissance angels of the American Dream. Eventually a number of these entities revealed some very disconcerting tendencies. Sathya Sai Baba (d.2011) became a focus of controversy, claiming to be a reincarnation of Shirdi Sai Baba (d.1918). Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh (d.1990) became notorious as a consequence of his therapy ashram at Poona, succeeded by his controversial commune in Oregon (his example was remote from Hazrat Babajan, the faqir of Poona who lived in a different era; also, Meher Baba, an Irani Zoroastrian born at Poona, was not in the same category, although afflicted by Paul Brunton; the Meher Baba movement has different presentations). The Eastern representatives became substantially outnumbered by the Western claimants to enlightenment, healing, empowerment, and integration.

California became the seedbed of notorious enthusiasms, cults, and lunacies. During the 1970s, almost any fad could quickly succeed in becoming a commercial attraction. New "therapies" became legion. The word "workshop" signified entrepreneurial new age excursions into supposed "higher consciousness."

The commercial offerings of the Esalen Institute were very influential. Critics were in perpetual wonderment at the consumption of doubtful activities and crazes. One of the most influential entities at Esalen was Dr. Stanislav Grof, a resident for many years during the 1970s and 1980s. His theories about psychedelic experience and hyperventilation are not accepted in conventional medical quarters (see further Grof Therapy and MAPS on this website).

Such books of Grof as LSD Psychotherapy (1980) aroused enthusiasm in Esalen circles. This situation contrasted, in other sectors, with strong queries and denials as to Grofian validity. Grof's subsequent book The Adventure of Self-Discovery (1988) amounted to a promotion of his new opportunist therapy Holotropic Breathwork, commercially administered via the auspices of Grof Transpersonal Training Inc. Some investigators were very critical as to why that book was published by SUNY (State University of New York), who turned a blind eye to disadvantages of hyperventilation.

The Findhorn Foundation was the major point of entry for Esalen enthusiasms into Britain. This export trend was facilitated by 1980s affluence, also an international list of subscribers susceptible to entrepreneurial workshops. The advertised success of Stanislav Grof's trademark "therapy" (Holotropic Breathwork) during the period 1989-1993, at the Findhorn Foundation, masked suspicious events and casualties that were covered up at every step by the promoters. Hyperventilation is a dangerous exercise, whether or not attended by psychedelic enthusiasms.

I have related in other articles (and epistles) on this website how the Holotropic Breathwork problem was more realistically diagnosed outside the Foundation. An expert in forensic medicine at Edinburgh University was fortunately resistant to Grof Transpersonal Training Inc. The expensive hyperventilation "workshops" were nevertheless invested by believers and victims with an aura of unassailable authority, meaning the pronouncements of Dr. Grof.

In general, the "workshop" innovators often assumed "holistic" expertise. Some entrepreneurs referred to the holistic movement. These presumed experts claimed intuitive abilities, healing powers, ecological prowess, skill in resolving conflicts, shamanistic faculties, esoteric wisdom, self-development proficiency, and indeed numerous other variants of commercial enthusiasm. Critics remained unmoved, investigating what the holistic exemplars actually did and how much money they charged.

As a conglomerate trend, these practitioners claimed a form of dynamic spiritual education sufficient to change the world. This myth has been ongoing until the present day. Phrases like "personal and spiritual transformation" are ubiquitous in the sectors to which they appeal; however, the evidence of accomplishment is far more difficult to find.

Some analysts of the phenomenon concluded that "new age" developments basically represented the response of persons desiring a form of alternative religion to Christianity, which was increasingly viewed as an inadequate doctrine. Others say that, although this theory appears to have an element of truth, there is the complexity involved of two basic new age contingents: the affluent clientele and the entrepreneurial "experts." The affluent clientele in Western countries clearly do want a different doctrine to that found in traditional religion. They are too easily content with commercial workshop fads and "holistic" lore.

The nominally holistic enthusiasts have often depreciated traditional education (in schools and universities) as being inferior and anti-intuitive. Many of them have decried analysis and critical appraisal as evils. Science is particularly abhorred in their ranks, while scholarship is also ridiculed as being irrelevant. The sense of history, in some alternative circles, has been so vestigial that records of recent events do not exist. Except, that is, amongst the critics who have reasons for strong objection to disconcerting "holistic" codes.

Traditional philosophy is another target of the alternativism. The former is accused of being based on logic and analysis, factors supposedly anti-holistic and therefore to be discounted. The reasoning involved here has been considered almost beyond belief by close assessors. In a "holistic" world where there is no due analysis, no real sense of history, and no trained reporting, almost anything suspect can take control. Critics say that this drawback is a more or less daily occurrence in the circles under discussion.

2. Richard Tarnas and the Passion

There are extensions of alternativism more literate than the generality. Some "new age academics" have contributed theories which are articulate, but nevertheless in doubt elsewhere. For instance, Professor Richard Tarnas authored a widely read book The Passion of the Western Mind (1991; repr. 1996). This work includes a review of modern Western philosophy, accompanied by a theme of contemporary "epochal transformation" (p. xii). The message is that Copernican astronomy, the metaphysics of Rene Descartes (1596-1650), and Kantian epistemology were milestones en route to the contemporary spiritual alienation. More specifically, those three developments are described in terms of "a threefold mutually enforced prison of modern alienation" (Tarnas 1996:419).

Descartes is a familiar target of other alternativists like Fritjof Capra. The despised "Cartesian-Newtonian" paradigm has more detail in the old age versions. There are different versions of what Descartes believed. He certainly represented a transient phase in physics, while exercising a more enduring influence in the vivisection horrors attaching to biology, zoology, and medical science. See Animal Ethics, Animal Rights.

The basic complaint broached by Tarnas, in his controversial Epilogue, amounts to: "The world revealed by modern science has been a world devoid of spiritual purpose, opaque, ruled by chance and necessity, without intrinsic meaning" (Passion, p. 418). A citizen is easily able to agree with that verdict. However, there are different ways of seeking a solution to the problems involved.

Descartes is assessed by Tarnas in terms of "the crucial midpoint between Copernicus and Kant" (ibid., p. 417). The truth is that Descartes was not an academic professor like Kant, although he was a scientist, and perhaps more of an empiricist than a philosopher. His confusing mechanist doctrine suited the scientific temper of his era in the revolt against religious dogmas. According to some writers, Descartes was ideologically eliminated by Kantian empirical reasoning, along with others whom Tarnas barely mentions in the alienation theory. Descartes was really the midpoint between Bacon and Spinoza, the latter being almost invisible in Passion.

Some say that Tarnas was rivalling the popular book by Capra entitled The Turning Point (1982), which more aggressively downgraded traditional philosophy in favour of the "holistic" approach, in this instance a version of systems theory, or "the new systemic conception of life." Capra was noticeably benign towards Grof LSD theory, his attitude being symptomatic in several respects of Esalen "progressivism." Cf. Capra, The Hidden Connections (2002), which makes no mention of Grof, instead favouring Anthony Giddens and Jurgen Habermas as reference points (pp. 67ff.). More recently, Capra is well known for selling the Capra Course online, following the general "holistic" practice of courses and fees.

The Tarnas version of Western philosophy is comparatively amiable. He commences with a brief version of early Greek exemplars, culminating in Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle. The distinctions between Aristotle and Plato are drawn. Some credit is given to both, resulting in the reflection: "We find a certain elegant balance and tension between empirical analysis and spiritual intuition, a dynamic beautifully rendered in Raphael's Renaissance masterpiece The School of Athens" (Tarnas 1996:68).

The Stoics and Neoplatonists receive rather less profile. Plotinus gains only two pages, and of a generalised nature. Further, the Muslim falasifa are missing; the omission is a common failing in presentations of Western thought (despite the fact that Ibn Rushd was active in Spain). The Christian Schoolmen come under review, with the lion's share of attention falling to Aquinas. Roger Bacon is only fleetingly mentioned. A chapter on the Renaissance is followed by others on the Scientific Revolution, the favoured subjects here being Copernicus, Galileo, and Kepler, with reference to Isaac Newton. The accompanying "philosophical revolution" is treated in terms of Francis Bacon and Descartes, which is a basically conventional view.

Tarnas appropriately observes that philosophy, in the classical era, "held a largely autonomous position as definer and judge of the literate culture's world view" (ibid:272). In the medieval period, Christianity replaced that autonomy, "while philosophy took on a subordinate role in the joining of faith to reason" (ibid). In contrast, the modern period saw philosophy transfer to science and "establish itself as a more fully independent force in the intellectual life of the culture" (ibid).

For whatever reason, Tarnas makes only very fleeting reference to Spinoza, whose ideological trajectory has elsewhere been viewed as significant, despite the enigmatic nature of some components. Indeed, there is very little information supplied in Passion about Leibniz also, giving the impression that such pre-Kantian thinkers were of small relevance. Instead, there are rather more substantial allocations favouring Freud and Jung, a gesture reflecting the contemporary preoccupation with a type of psychology. The theories of C. G. Jung have created much confusion. Tarnas is clearly an enthusiast, not a critic in that direction. The word archetype is generously listed in the index of Passion to a degree quite overshadowing a fair number of philosophers.

A section entitled "Self-Critique of the Modern Mind" dwells upon John Locke (1632-1704), Bishop Berkeley, David Hume, and Immanuel Kant (1724-1804). Tarnas observes differences between the British empirical tradition and Continental rationalism of the seventeenth century. The former was triumphant over the latter, according to many conventional assessments.

Locke opted for the immediacy of sensory experience, being influenced by the empiricism of Isaac Newton (1642-1727) and the Royal Society. The provocative idealism of George Berkeley (1685-1753) is variously classified as empiricist and Cartesian. Tarnas comments that "in effect, while Locke had reduced all mental contents to an ultimate basis in sensation, Berkeley now further reduced all sense data to mental contents" (Passion, p. 335).

The scepticism of David Hume (1711-76) early opposed the idealism of Berkeley. The theory here moved back to sense impressions. More radically, Hume "concluded that the mind itself was only a bundle of disconnected perceptions, with no valid claims to substantial unity, continuous existence, or internal coherence, let alone to objective knowledge" (Passion, p. 340; cf. Shepherd 2005:224-38, for a critical version of Hume). A form of extreme scepticism was expressed by Hume, who was inclined to deny the validity of inductive reasoning.

The outlook of Hume has been subject to varying shades of interpretation. He can be credited with a genuine interest in psychology, his version nevertheless being in question. In his Treatise on Human Nature (1739-40), Hume stated that "reason is, and ought only to be the slave of the passions." This hedonistic assertion does not necessarily follow from his more credible deduction that emotion (or desire), and not reason, governed human behaviour. Due reason has to be cultivated, and should not be a slave.

Hume was blocked from obtaining the Chair of Logic at Glasgow University. Charged with atheistic heresy, he was afterwards acquitted. Yet if "labelling Hume as an 'atheist' is misleading," he was certainly very critical of religion (quote from Paul Russell, Hume on Religion, 2005). With regard to scientific implications, Bertrand Russell complained that Hume "arrives at the disastrous conclusion that from experience and observation nothing is to be learnt" (History of Western Philosophy, second edn 1961, p. 645).

l to r: David Hume, Immanuel Kant |

Tarnas goes into more detail with Kant, who is effectively his major reference point in philosophy during the modern period. Kant was concerned to offset Hume's scepticism, while at the same time being influenced by that negativity. Kant strongly believed in Newtonian science; however, in assimilating Hume, he transited from what some describe as the German rationalism associated with Leibniz. "His solution was to satisfy the claims of both Hume and Newton" (Passion, p. 342). That assessment may be considered correct, even if Kant does not gain full profile in the neo-Jungian version.

Kant's Critique of Pure Reason (1781) was composed in the academic milieu, unlike earlier philosophical works. There is the unventuresome insistence, in the Critique, that anything not apprehended by sensory impressions cannot be experienced. Falling in line with Humean scepticism, Kant may himself have been more of a sceptic than is often believed. He stated:

The principles resulting from this highest principle of pure reason will, however, be transcendent in relation to all appearances, that is to say, it will be impossible to make any adequate empirical use of this principle. (Kant, Critique of Pure Reason, p. 241)

This pedagogic angle meant that the world of phenomena is the only field of possible knowledge; in contrast, the noumenal or "transcendental" world is not accessible to human experience. "The end result of his [Kant's) critical labours may seem to resemble Hume's skepticism" (Kuehn 2001:246).

Views have differed as to the extent of Kant's Christian bias; he was apparently far more of an Enlightenment intellectual than anything pietist. He relied solely on rational criteria in his writings. "It was clear to anyone who knew Kant personally that he had no faith in a personal God; having postulated God and immortality, he himself did not believe in either" (ibid:3). One could perhaps connect that psychology with the basic message of his critical philosophy:

God, immortality, and other such metaphysical matters could never become phenomena; they were not empirical; metaphysics, therefore, was beyond the powers of human reason. (Passion, p. 341)

Religious faith was left free in this argument. Only "pure reason," of the deceased gentlemanly amateurs, was sent to ideological jail by the academic professor. One of those amateurs (Spinoza) was a heretical Jew, still largely subterranean when Kant wrote his Critique.

In a subsequent work, The Critique of Practical Reason (1788), Kant was committed to morality. His moral philosophy implies that "morality is the exclusive domain of reason." The second Critique was one in which "from the point of view of traditional theology, Kant turned things upside down" (Kuehn 2001:312, 314). This was a purely rational exercise in which mysticism is debunked.

Kant affirms that even the Stoics went astray in proclaiming 'virtue' as being fully attainable in the present life of the wise man.... In Kant's view, holiness cannot be attained by any creature.... Plato is duly castigated for having entertained an 'extravagant pretension' to a 'theory of the supersensible'. (Shepherd 1991:147)

However, Kant's secular morality is commendable; he is much superior to Hume, Nietzsche, and various others on that score. His Groundwork of the Metaphyiscs of Morals (1785) demonstrates a convergence with Cicero (the Stoic), and furthermore opposed class biases (Kant was the son of an artisan). "Any attempt to defend or justify social differences by appealing to morals must be rejected as well; the conservative status quo must be challenged" (Kuehn 2001:282).

Kant pursued an a priori ideal of pure reason in the moral sphere, contrasting with the earlier pure reason of Leibniz and his predecessors (relating to metaphysics). Kant's ideal emerged in the form of what he called (in German) the categorical imperative, meaning "the unconditional command of morality," even though his Enlightenment reasoning imposed a belief that "the ultimate condition of the possibility of morality cannot be understood" (ibid:286). Again perhaps a rather cordoning conceptualism, the entire presentation marked by a notoriously convoluted style of expression.

Everyone finds his writing difficult; it is nearly always obscure, and sometimes it borders on the impenetrable.... his work, even after two hundred years, is still unknown territory to most educated people.... he [Kant] is widely regarded by serious students of philosophy as the greatest philosopher since the ancient Greeks. (Magee 1988:185-186)

Yet despite his moral worth and academic intensity, the cordoning and empirical Kant is not particularly enviable for his situation of mental confinement to sensory impressions. By 1777, he was a hypochondriac worried about his constipation. Moreover, "Kant felt that it was ultimately the obstructions of the bowels that caused distractedness and periods of confused thinking from which he was beginning to suffer. These complaints, though comical-sounding, made his life quite miserable" (Kuehn 2001:239).

In contrast to some citizen complaints, the Kant cameo by Tarnas is relatively indifferent to contrasts in career background. Professor Tarnas writes in an academic idiom neglecting to emphasise that Kant was the first major philosopher to fill a professorial role. Tarnas does usefully indicate that, in later generations, the academic pursuit of philosophy tended to become circumscribed and largely unintelligible to citizens.

For any citizen philosopher to stand up and contest circumscribed and unintelligible matters today, the effort could too easily amount to being erased from Wikipedia by a "postmodern" strategy of pseudonymous cult supporters assisted by an officious (if anonymous) academic specialist in plant biology, the latter explicitly ignorant of (and disinterested in) the issues at stake. The sympathetic academic philosopher (Simon Kidd), who contested this censoring decision (using his real name), was outvoted by web anonymity. This point is demonstrable to readers via recorded occurrences expunged by the Wikipedia administrative system (see Wikipedia Anomalies and Misinformation). Suppression did not end with the Spanish Inquisition; to some extent, cordon is now an American speciality, rather than a Eurocentric one.

4. Official Death of Metaphysics

According to the ingenious reasoning of Kant: "Although one could not know that God exists, one must nevertheless believe he exists in order to act morally" (Tarnas, Passion, p. 349). A long list of celebrated names is supplied by Tarnas, meaning writers who had the effect of "altogether eliminating the grounds for subjective certainty still felt by Kant" (ibid:351). Not merely the radicals Marx and Nietzsche, but academics like Heidegger, Wittgenstein, Levi-Strauss, Foucault, Popper, Quine, and Kuhn. This process of denial led to the postmodernist view that underlying principles of experience are not absolute and timeless, but "varied fundamentally in different eras, different cultures, different classes, different languages" (ibid). Still at issue is whether such views comprise an accurate judgement of reality.

Yet at first, there were idealist responses to the Kantian conceptualism. German thinkers, most notably Georg W. F. Hegel (1770-1831), "constructed a metaphysical system with a universal Mind revealing itself through man" (ibid:351). A big drawback here was the Eurocentric tendency of Hegelian theory. Hegel was an elite professorial entity exercising a verbose dialectic that did not create the most readable corpus in the history of philosophy. "Often Hegel's historical judgments seemed peremptory, his political and religious implications ambiguous, his language and style perplexing" (ibid:382).

Nevertheless, Hegel did inspire "a renascence of classical and historical studies from an Idealist perspective" (ibid:381). Academic philosophy thereafter contracted into contentment with the minutiae of language and conceptualism well known in twentieth century works. Metaphysics was dead, having been dismissed according to standards of the prevalent laziness and convenience in psychological endeavour, a situation ideal for someone like Bertrand Russell (1872-1970), whose private life was a problem often criticised. The Tarnas commentary states that:

As philosophy became more technical, more concerned with methodology, and more academic, and as philosophers increasingly wrote not for the public but for each other, the discipline of philosophy lost much of its former relevance and importance for the intelligent layperson, and thus much of its former cultural power. (Tarnas, Passion, p. 354)

Meanwhile, another trend had been operative. According to Tarnas, Romanticism was the polar complement to the Scientific Revolution, both sharing common roots in the Renaissance, with the former preferring aspects of experience suppressed by the eighteenth century Enlightenment. German and British names figure prominently in the list of Romantic exponents, from Goethe and Herder to Blake and Byron. "While the scientist sought truth that was testable and concretely effective, the Romantic sought truth that was inwardly transfiguring and sublime" (ibid:367). There were idiosyncrasies in both camps, and some lunacies in Romantic ranks, which is a citizen observation.

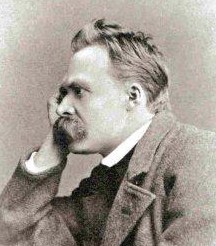

Friedrich Nietzsche |

The Tarnas account describes Nietzsche (1844-1900) as a Romantic. There is strong scope for disagreement in the sense of eulogy afforded. Tarnas describes Nietzsche in terms of "a uniquely powerful synthesis of titanic Romantic spiritual passion and the most radical strain of Enlightenment skepticism" (ibid:370). This verdict represents an excessive enthusiasm quite often found. It is much easier to credit that "in Nietzsche, as in Romanticism generally, the philosopher became poet" (ibid:371). Exactly what kind of poet requires to be ascertained amidst the morass of fictions attending this figure.

Nietzschean concepts such as the" superman" and "will to power" reveal a basic confusion. This need not be ascribed to Romanticism but, instead, to the psychology of the subject. In particular, the superiority complex of Nietzsche is expressed in passages needing due critical assessment. For Nietzsche, the violence of Napoleon was preferable to the supposed herd instinct for less damaging manifestations of social deportment. The contempt of Nietzsche for the Indian untouchables (or Dalits) became known to critical Indologists. In citizen terms, he was an elitist prig living in an academic situation of privilege that knew no sympathy for the working man and outcastes.

The elitism of Nietzsche demonstrates an acute and very objectionable drawback; this was not the usual class bias, but instead a "superman" power complex of manic dimensions. Opposing religious and secular morality, Nietzsche glorified the instincts, perhaps because he had visited a brothel and there got into trouble; the aristocratic and bourgeois dimensions of license do not validate caste society. His stigma of "slave morality" can be strongly contested.

The Nietzschean will to power frowned upon four main contingents of slave morality: Christianity, the tradition of secular morality associated with Kant and other German philosophers, Socratic and related Greek philosophical traditions, and the herd morality of the unprivileged masses. The Indian untouchables were included in the stigma in his Twilight of the Idols (1889), in which caste tactics were approved by the atrocious nihilist. Living on a university pension, he [Nietzsche] had no sympathy for, or conscience about, the plight of so many persons less well placed than himself.... There are some pedagogues who blandly equate Nietzsche with Socrates in a theme of 'archetypal sacrifice' initiating epochal transformations in the history of the Western mind. (Shepherd 2004:244-5)

The last sentence abovecited refers to the archetypalism of Richard Tarnas (cf. Passion, p. 395). The archetypal exegesis is an illustration of extreme confusions created by Jungian theory. Nietzsche tragically became insane in his last years. Critics have implied that he was psychologically maladjusted, also dangerous in his views, rather than being any kind of viable philosopher. Some lenient critics say that his early writing is of interest, while his later "oracular" works are disconcerting. "The bite of conscience is indecent," wrote Nietzsche. Such assertions are not to be commended.

In a discussion of relevance, Professor J. P. Stern (an expert on the subject) stated that Nietzsche "is most emphatically not a democratic philosopher." This judgment was explicitly in agreement with the description supplied by Professor Bryan Magee: "He [Nietzsche] believed... that the individual great man, the hero, should be a law unto himself, should not be hamstrung by consideration for lesser mortals, and still less by petty rules and regulations" (Dialogue with J.P. Stern, in Magee 1988:237).

The sheer nonsense expressed by partisans of the "gentle Nietzsche" is a sobering factor. Enormous public confusion has been caused by some of his admirers, who are effectively elitist champions of slavery, aristocratic superiority, and white supremacy:

These 'gentle Nietzscheans' overlook his passionate opposition to the socio-political values and institutions of modernity, and the counter-revolutionary implications of his revolutionary ideas. Praising him [Nietzsche] as a champion of (self-) liberation, they ignore the severe restrictions he places on the idea of human emancipation.... There are more than 300 references to slaves, slavery and similar terms in Nietzsche's works. The vast majority of these affirm the necessity of human bondage. In Beyond Good and Evil he wrote: "Every enhancement of the type 'man' has so far been the work of an aristocratic society - and it will be so again and again - a society that believes in a long scale of orders of rank and differences in value between man and man, and that needs slavery in some sense or other." (Martin A. Ruehl, Nietzche's Dangerous Thinking, 2018)

Discrepantly perhaps, the brief Tarnas chapter entitled "At the Millenium" selects the figure of Max Weber (1864-1920) along with Nietzsche, Jung, and Martin Heidegger (1889-1976), as suitable indicators of the contemporary epochal transformation denoted. There are marked differences between Weber and the other three. For instance, Nietzsche, Jung, and Heidegger are all associated with Nazism in different ways (and in controversial arguments), unlike the sociologist Weber. Tarnas does not mention this less romantic factor. Instead he approvingly cites (Passion, p. 413) from Thus Spake Zarathustra, the "Romantic" novel by Nietzsche that has no relation to the ancient Iranian prophet of Zoroastrianism. Tarnas does not make any distinction between a literary curiosity and Iranian religion, as his index reveals. Perhaps the envisaged epochal transition will lead to insanity and the neglect of due knowledge about the history of religion.

"Our moment in history is indeed a pregnant one" says Tarnas on the same page as his quote from Thus Spake. Abortion is a common resort in the "postmodern" society, so even the archetypal moment may transpire to represent miscarriage rather than birth. The "boldness, depth, and clarity of vision" evoked in the same passage may decode to total blindness induced by social and pedagogical misconstructions.

In his preface to Passion, Tarnas says: "Today the Western mind appears to be undergoing an epochal transformation, of a magnitude perhaps comparable to any in our civilisation's history" (Passion, p. xii). Other analysts are inclined to view contemporary tendencies in terms of a potential breakdown of civilisation, accompanied by climate change (which is not the only problem). Due education, and ecological rectification, are not realistically in sight.

Tarnas does qualify his reflection by stating his belief that "we can participate intelligently in that transformation only to the extent to which we are historically informed" (ibid). Historical information is not the same as Romantic sentiment, hero mythology, archetypal fantasy, and psychedelic distraction. The contemporary transformation is a mirage produced by "holistic" sentiment.

The Passion is more convincing in describing the "crisis of modern science." Some remarks are quite graphic. The "classical Cartesian-Newtonian cosmology" collapsed as a consequence of fresh discoveries in physics; further problems of interpretation arose.

By the end of the third decade of the twentieth century, virtually every major postulate of the earlier scientific conception had been controverted.... The solid Newtonian atoms were now discovered to be largely empty.... Matter and energy were interchangeable. Three-dimensional space and unidimensional time had become relative aspects of a four-dimensional space-time continuum. Time flowed at different rates for observers moving at different speeds. Time slowed down near heavy objects, and under certain circumstances could stop altogether. The laws of Euclidean geometry no longer provided the universally necessary structure of nature.... There was now no coherent conception of the world, comparable to Newton's Principia, that could theoretically integrate the complex variety of new data. Physicists failed to come to any consensus as to how the existing evidence should be interpreted with respect to defining the ultimate nature of reality. (Tarnas, Passion, pp. 356-8)

The mood of relativism (and scepticism), gaining currency by the 1970s, reacted to the dependency upon belief in science. The crux of the matter is that scientists do not know the nature of reality, while academic philosophers have failed to explain this unknown priority in ongoing or assimilable terms. Attempts to do so are often discredited, or regarded as totally hypothetical. The postmodernist resort to forms of relativism is no proof of competence.

Meanwhile, the technological offspring of science continue to exploit nature to a degree that is generally concealed. Genetic engineering is only one of the offensive manifestations of incompetence and commercial enterprise.

The Tarnas version of postmodernism says that this phenomenon "varies considerably according to context" (Passion:395). Ingredients are described as ranging from "pragmatism, existentialism, Marxism, and psychoanalysis to feminism, hermeneutics, deconstruction, and postempiricist philosophy of science" (ibid). These are academic trends, of course; the public are generally fed with commercial entertainment, thus generally lacking cognisance of the ideational influences at work in society. However, the academic resorts are often flawed, with "a perspectivism rooted in the epistemologies developed by Hume, Kant, Hegel (in his historicism), and Nietzsche" (ibid:397).

The "postmodern" problem of scepticism is stated to be strongly influenced by the analysis of language, with many contributing sources such as Nietzsche, Peirce, Ferdinand de Saussure, Wittgenstein, Heidegger, and Foucault. Strong criticism can be levelled at some of these influences, also the deconstructionism of Jacques Derrida (1930-2004), whose tactic is described in terms of "challenging the attempt to establish a secure meaning in any text" (ibid:398). The general postmodernist conceptualism is assessed in terms of "applying a systematic skepticism to every possible meaning" (ibid:399).

More pointedly, the target of postmodern aspersions is the Western philosophical tradition since Plato. "The whole project of that tradition to grasp and articulate a foundational Reality has been criticised as a futile exercise in linguistic game playing, a sustained but doomed effort " (ibid:400).

My web entry on Jacques Derrida included reference to the opposition against him within academic ranks. The friction in viewpoint is obviously relevant to dwell upon, contrary to some accounts which do not mention the opposition. My basic view on deconstruction is one of strong resistance. If there are no secure meanings in texts (however the contention is worded), deconstructionist texts may also be insecure, or for that matter, all academic texts. Truth values are so elusive in the general postmodernist ideology that anything is at best only personal or cultural taste, quite relative to any permanent achievement.

In the current deceptive climate, one could almost be relieved to hear that "there is no 'postmodern world view,' nor the possibility of one; the postmodern paradigm is by its nature fundamentally subversive of all paradigms" (Passion:401).

There is, of course, a catch here. Many years later, the subversive paradigm is now extensive. Furthermore, postmodernism discernibly includes (however indirectly) the "new age" contingents and cults, which thrive in the general ignorance and confusion. Tarnas does not say this, instead commenting: "There remain few, if any, a priori strictures on the possible, and many perspectives from the past have reemerged with new relevance" (ibid:403). He refers to forms of intellectualism, Romanticism, and of Eastern and Western religion, including "Neolithic European" plus "Gnosticism and the major esoteric traditions."

Tarnas does not mention the extreme confusions caused by this new wave of the supposedly antique. He was writing during the 1980s, at a time when, for instance, the Rajneesh sect was demonstrating strong antisocial tendencies in Oregon, a retrogressive feat accompanied by alternative therapy and the exaltation of Nietzsche's Thus Spake Zarathustra (favoured by Rajneesh), which had become a cult fad of presumed supermen. According to an American sociologist, "Rajneesh's vision of the new man was based upon Nietzsche's ideal of the individual who is absolutely free of the constraints of family, church, governments, and cultures" (Shepherd 2004:62, citing Professor Lewis Carter).

We are told by Tarnas that "the postmodern collapse of meaning has thus been countered by an emerging awareness of the individual's self-responsibility and capacity for creative innovation and self-transformation in his or her existential and spiritual response to life" (Passion, p. 404). This may indeed be an advance upon nihilism, yet there are pronounced drawbacks to the enthusiasm. I have seen the word transformation enticingly employed so many times during the last forty years that my response has long been one of nausea at the persistent assumption denoted. Far too many deluded cult recruits have believed they were transformed; alternative therapists have exploited that belief to a staggering extent in another sphere; the "creative innovation" has included ecobiz and numerous other doubtful capitalist ruses.

The "postmodernist" themes are said to have rooted in social sciences and the humanities, in America and other countries. Many academic philosophers do not appear to subscribe to those themes. Indeed, the year after Passion of the Western Mind was published, in 1992 a petition of disapproval was filed against Derrida by eminent international Professors, in an unsuccessful attempt to prevent his gaining further honorary credentials. The academic situation is far more complex than some generalising accounts imply. For instance, in Britain, analytical philosophy has often been resistant to the Continental "poststructuralism" associated with Derrida and Foucault. Not merely the despised metaphysical matters, but also science and scholarship, are said to be at issue in the extreme postmodernist arguments propounded.

A rather monotonous postmodernist theme is that objective truths are a myth, only local beliefs being in evidence. Scientists have understandably reacted to such undermining insistences. See Sokal and Bricmont 1998, repudiating the idea that science amounts to social construction, i.e., meaning something improvised and equivalent to myth. Fashionable postmodernist nonsense has achieved the status of profundity (see also Sokal 2008). A basic point made by the protest is that scientific discovery occurs across local and relative social and linguistic boundaries, the databank thus amounting to something substantially real and objective.

By extension, there may well be philosophical (and even metaphysical) truths that are similarly elusive of the "local belief" lore. The necessary "universalist" endeavour is currently in low profile. What is largely visible instead is the popular "new age" of magic and presumed metaphysical relevance, in which science and scholarship are frequently dismissed as distractions, while philosophy is regarded as a folly of superfluous logic (indirect or partial convergences of magic and "therapy" with academic postmodernism do exist, therefore). The degree of knowledge about the past is often nil, or nearly so. The commercial "workshop" is very often the ideal in sectors prone to entrepreneurial exploitation, which manipulates factors of emotion and belief.

8. Jung and Pseudo-Metaphysics

One of the most celebrated and confusing writers in the twentieth century was Carl Gustav Jung (1875-1961). His views have been copied and regurgitated in countless formats, to the extent that he is described as the virtual founder of the new age. Richard Tarnas is one of the Jung votaries, an orientation quite evident from statements made in Passion; he was evidently a believer in the view that "archetypes" govern mental functioning. Moreover, the underlying tendency of that author's exposition is perhaps revealed by his reflection concerning a "Romantically influenced science," where he adds: "The most enduring and seminal proved to be the depth psychology of Freud and Jung, both deeply influenced by the stream of German Romanticism that flowed from Goethe through Nietzsche" (Passion, p. 384; cf. Shepherd 2004:23-38, for a critical version of Jung).

Of the two celebrity names in psychology here elevated by Tarnas, Jung was far closer to Nietzsche. There are some other factors also involved.

With his philosophical grounding in the Kantian critical tradition rather than in Freud's more conventional rationalist materialism, Jung was compelled to admit that his psychology could have no necessary metaphysical implications. It is true that Jung's granting the status of empirical phenomena to psychological reality was itself a major step past Kant, for he thereby gave substance to 'internal' experience as Kant had to 'external' experience. (Tarnas, Passion of the Western Mind, p. 386)

The Jungian psychology became a pervasive "metaphysical" resort of the postmodern new age, via hundreds (and perhaps thousands) of overnight experts on the garbled lore of "collective unconscious." The popular reception of this lore was catastrophic for public discernment of tangible events in process.

In more academic sectors, the Jungian speculations were paralleled by strong relativist accents that have also been strikingly influential. Tarnas expresses a confusing version of the converging doctrines and opinions:

The postmodern philosopher's recognition of the inherently metaphorical nature of philosophical and scientific statements (Feyerabend, Barbour, Rorty) has been both affirmed and more precisely articulated with the postmodern psychologist's insight into the archetypal categories of the unconscious that condition and structure human experience and cognition. (Passion, p. 405)

The basic theme here is not convincing, at least to a citizen analyst unmoved by the confusions evident within academic and new age postmodernism. Jung is more well known than the other names mentioned. The philosophers Paul Feyerabend (1924-1994) and Richard Rorty (1931-2007) have also been very influential within intellectual circles, especially the former, whose acutely confrontational form of relativism manifested in the philosophy of science. Not everything Feyerabend said was questionable by any means; however, certain flippant emphases and attitudes were and are objectionable. "Anything goes" has more or less become the social norm.

In my first published book, I included a citizen riposte to Feyerabend. I still deny the underlying drift of his faulty logic (Shepherd 1983:169ff; Shepherd 1989:45ff.). The argument is not just about science, but about how philosophers think [and the tendency to new age relativism]. Some academics said at the time (1980s) that they had never known a contemporary citizen to comment in an annotated format upon such matters. The inherently flippant nature of some Feyerabendian statements is substantial enough, despite the adulation awarded in some endorsing academic sectors.

I should state here that I defended the empirical relevance of scientific method against certain nuances of Feyerabend's epistemological anarchism. There were also social factors involved in the loaded argument. For instance:

Feyerabend advocates a 'Free Society' in which anything goes in the commitment to universal standards, and in which science is treated as being of no more importance than any other subject or approach. In contrast, I maintain that we already have an open society in which virtually anything goes, to the detriment of true freedom and truly universal standards. (Shepherd 1983:169)

Many years later, the so-called free society (in both America and Britain) is far more unrestrained and violent, with confusions mounting about what is most real or most valuable. Big business dictates what goes (and what sells), more so even than the postmodernist innovators.

Some academics noticed a comment in one of the annotations to the book abovecited:

I cannot say that I disagree with everything Feyerabend says, but if Feyerabend can instate such axioms as a Professor of Philosophy at a well known university in California, then I can state that I am quite content to be considered an ordinary member of the public in Cambridge. (Shepherd 1983:191 note 285)

The American neopragmatism of Richard Rorty has been considered confusing by critics. Science and reason acquire a relativist complexion in his theory of life. "No area of culture, and no period of history, gets Reality more right than any other." Truth is elusive in such formulations. In a well known web video, Rorty states, "the less certainty we have, the better." Such an impoverishment is not considered desirable by everyone. Of course, certainty in some instances does transpire to be unfounded. However, philosophers and others should be more enlightened than yob society, which thrives upon uncertainties about justice.

10. Negotiating Contractions in Academe

Western philosophy can be viewed in a manner that is not fashionable amongst the diverse postmodernists. The polymathy of Leibniz is quite beyond most contemporary aptitudes. In brief, philosophy was adversely mutated by twentieth century developments which still chewed the cud of Hume's scepticism. The major pre-Kantian philosophers were not academics (though Hume tried to become one); the Continental "Rationalists" eschewed the scepticism deriving from Montaigne and other sources. The much later Continental academic wave, now so famous and influential, were the polar reverse of their origins.

It was not until the 20th century that nearly all outstanding philosophers were academics. This professionalisation of philosophy was sharply criticised early on by Schopenhauer as being bad for the subject, and has always been controversial, but it is now institutionally entrenched, and seems unlikely to be reversed. (Magee 1998:132)

In the face of monolithic institutionalism, the citizen thinker is not obliged to rest content with crumbs falling from the starvation diets of Heidegger, Derrida, Rorty, Alfred J. Ayer, Gilbert Ryle, and even Wittgenstein. A similar option of independence exists in relation to the neo-Hegelian format of Ken Wilber (i.e., AQAL). However, Wilber exists outside academe, or rather within the Integral Institute. Wilber tries to incorporate the postmodernist sceptics in his "integral spirituality," which he has also called "integral post-metaphysics." There is a contrasting argument not geared to integration.

The diet of postmodernist Michel Foucault (1926-84) extended to sadomasochistic eroticism in psychedelic milieux of California, conferring the ability to contract AIDS, which proved fatal. Academic deportment can sometimes be questioned (Shepherd 2004:245ff).

The American postmodern media has overshadowed some other countries, while being keen to assimilate British scepticism, Continental relativism and nihilism, and the more commercial Jungian theory acquired from Europe. The dissenting British (or Irish-English) citizen philosopher is, in contrast, free to take a different route that can instead feast upon the original pre-Kantian exponents of modern Western philosophy, and the rather substantial legacy of international thought existing before Descartes. The history of science is incorporated in this repast (cf. Psychology in Science). The focus can simultaneously probe more recent events in philosophy and sophistry from Kant onwards.

The ongoing history of religions (from prehistoric eras to the present) is a relevant accompaniment for intellectual nutrition (cf. my Minds and Sociocultures, 1995), not least because the contemporary knowledge of that subject is frequently almost nil. Archaeology is an empirical ballast (Shepherd 1991:77ff, 156). A form of citizen sociology or sociography can also be useful for due analytical and social health. Fashionable antagonism to science is not a requisite. However, strong critique is relevant for the extensive technological capitalism and laboratory horrors.

11. Avoiding a Neo-Jungian Hazard

Anthropographic citizen recourse detours a major obstacle created by commercial neo-Jungian events. That hindrance is demonstrated in the Epilogue to Passion. The main text here comprises a review of entities and trends. The underlying affiliation of Richard Tarnas does not emerge until the closing pages.

The most epistemologically significant development in the recent history of depth psychology, and indeed the most important advance in the field as a whole since Freud and Jung themselves, has been the work of Stanislav Grof. (Passion, p.425)

There is also the enthusiastic assertion that (neo-Jungian) Grof theory has major implications for philosophy. Readers are further told that "the unexpected upshot of his [Grof's] work was to ratify Jung's archetypal perspective on a new level" (ibid:425). The Tarnas account was celebrated by Grof partisans. The envisaged epochal transformation, strongly implied in Passion as a contemporary occurrence, has persistent Grofian overtones in the alternativist sector associated with the California Institute of Integral Studies (where Tarnas is influential).

The Tarnas worldview thus demonstrated an underlying orientation with the controversial Esalen Institute. This is not surprising, given that Tarnas was formerly director of programmes at Esalen, where he lived for ten years, alongside Grof and others. His 1976 Ph.D. thesis was favourably committed to LSD psychotherapy.

In his introduction to The Secret Chief, a web text dating to the 1990s, Stanislav Grof stated: "Particularly valuable and promising were the early efforts to use LSD psychotherapy with terminal cancer patients. These studies showed that LSD was able to relieve severe pain, often even in those patients who had not responded to medication with narcotics. In a large percentage of these patients, it was also possible to alleviate or even eliminate the fear of death, increase the quality of their lives during the remaining days, and positively transform the experience of dying." (The Secret Chief, available at www.maps.org, is noted for celebrating the illegal activities of an experimenter in LSD therapy)

Critical assessments do not tally with Grof's optimism. Here is a non-partisan report:

Grof describes how his [terminal cancer] patients, dosed with LSD, 'spent hours in agonising pain, gasping for breath with the colour of their faces changing from dead pale to dark purple. They were rolling on the floor and discharging extreme tensions in muscular tremors, twitches and complex twisting movements.... there was often nausea with occasional vomiting and excessive sweating'.... At Spring Grove Hospital a total of one hundred [terminal cancer] patients were pressed into the LSD torture programme which Grof called 'research,' though criminal license is probably a more scientific description. 'Given that the patients were all deceased within months, no study of the long-term consequences of this therapy was undertaken.... Grof, his many prominent supporters, and the National Institutes of Health, never questioned the ethics of using human subjects in this type of research'. (Shepherd 2005:13, citing Curry 2002)

The psychedelic torture pills are evidently not something to welcome, either in normal states or in severe illness. As an ideological extension, the archetypal theme associated with Jung has been a pervasive alternative resort, employed in very numerous "workshops" for the affluent clientele, many of whom have probably never read Jung in sufficient detail to ascertain the relevance of controversial theories.

Critics of the Tarnas format underline another emphasis that is not universally agreed upon. Tarnas stated this contention in terms of: "The evolution of the Western mind has been founded on the repression of the feminine" (Passion, p. 442). I have already commented upon that neo-Jungian accusation, to quote: "We are thus presented with a popular idea commercialised at places like the Esalen Institute" (Shepherd 2004:19). The women repressed by the Grof-influenced Findhorn Foundation were critics of holotropic breathwork, a hyperventilation technique which created many victims (including women). The major female critic sent an urgent letter to Grof while he was visiting the Foundation. He failed to respond, obviously allergic to the criticism. Other parties have found that "holistic" figureheads suppress all objections to their activities.

Holotropic breathwork was strongly associated by partisans with LSD psychotherapy, another speciality of Grof promoted as a surpassing achievement. Citizens repressed by psychedelic personnel, and their supporters, are not obliged to agree with the lazy mysticism of academic LSD ingesters. The LSD trend, commencing in 1960s academic ranks, was thereafter sustained in those indulgent status circles. That misleading trend claims sensational progress influencing society, ignoring the truth about disastrous reverses.

12. Findhorn Foundation Holistic Censorship

Esalen themes (plus books by Grof and Tarnas) have been influential at "holistic education" centres like the Findhorn Foundation (Moray, Scotland). I am not a stranger to realistic data concerning the repressed feminine, having been acquainted at firsthand with three female dissidents who were suppressed and stigmatised by the Findhorn Foundation, in a manner that can scarcely be forgotten. Even legal complaints made no difference to the severely repressive attitude of the Foundation, an organisation which furthermore attempted in solicitor correspondence to deny extant membership details, a fact which goes very much against them. See further Kate Thomas and the Findhorn Foundation and my Letter to Robert Walter MP.

The Findhorn Foundation College (FFC) proclaimed on the web an expertise in "holistic education," presuming an all-rounded sense of accomplishment. In a web ad for a 2010 semester, the unconventional College asserted:

Integrating academic and experiential learning, the programme is based in the Findhorn Ecovillage, which provides a tangible demonstration of the links between the spiritual, social and economic aspects of life.... Students engage in daily seminars with faculty, experience living education through practical work in the community, and explore themes relevant to our times such as spiritual practice, sustainable and systemic design & thinking, and group process & conflict resolution. (The Human Challenge of Sustainability: Findhorn Community Semester at www.findhorncollege.com, accessed 12/06/2010)

This form of alternative operation has to date ignored and suppressed British female dissidents for many years, the ongoing theme of "conflict resolution" being interpreted elsewhere as a convenient facade for funding. The presiding agents in this situation now have the reputation of "new age brahmins," the affirmative caste who never concede errors or wrongs. The adverse reflection is strongly associated with aggressive American and Canadian "workshop" sponsors who tend to assume sovereignty in judgment.

The FFC were keen to enroll American college students, advertising some glowing comments from that semester category. For instance, there is the reported phrase: "What went well for me was being treated like a human being with a heart and a soul as well as a mind." Dissidents from the Findhorn Foundation were not even permitted to have a mind, being censored as unworthy of review and suited to oblivion. A noted dissident book (Castro 1996) was for many years routinely dismissed as having no validity by "holistic workshop" entrepreneurs with a vested interest in jettisoned facts.

One can here mention, by way of complement, that a precedent to the FFC was the ill-fated FCIE (Findhorn College of International Education), a short-lived enterprise of 1996. Ambitions of the FCIE faculty (Foundation personnel) were negated by the situation of enrolled American university students, who rebelled against the inadequate "holistic education" administered to them. See further Propaganda Tactics (2008).

An extension of this situation applies to the Scientific and Medical Network, an alternative organisation in England led by David Lorimer, who has promoted Grof and his disciple Christopher Bache. See my Letter of Complaint to David Lorimer (2005).

Meanwhile, Richard Tarnas became Professor of philosophy and psychology at the California Institute of Integral Studies (CIIS), which likewise featured Dr. Grof as a member of staff, to the accompaniment of Grof Transpersonal Training Inc. The books of Dr. Grof continued to emphasise the importance of his holotropic therapy, which he interpreted as "moving toward wholeness." The latter phrase appeared on the cover of his Psychology of the Future (2000).

The second book of Professor Tarnas was Prometheus the Awakener (1993). This work celebrates the astrological significances of Uranus, and moreover, strongly suggests that astrological phenomena influence the existence of both individuals and societies.

Archetypal astrology achieved elevation in a third book by Tarnas entitled Cosmos and Psyche: Intimations of a New World View (2006). Some of his readers were disconcerted by the format. Nevertheless, the alternativist British organisation called the Scientific and Medical Network awarded Cosmos and Psyche their Book of the Year Prize. In this controversial volume, Tarnas favours such themes as Jungian synchronicity, archetypal theory, and (rather pronouncedly) the Uranus-Pluto Cycle. The Beatles, in their 1960s activity, are described in terms of "Saturn return transits" (p. 122). Professor Tarnas is often identified as an astrologist.

Earlier versions of astrology were in circulation amongst the Greek and Roman philosophers, notably the Stoics. "Platonists similarly held the planets to be under the ultimate government of the supreme Good, but tended to view the celestial configurations as indicative rather than causal, and not absolutely determining for the evolved individual" (Passion, p. 84). Astrological fatalism was totally rejected by later thinkers. Elements of a scientific reformist belief in the subject were existent during the early phase of the Royal Society (ibid:486-7).

During the 1970s, in collaboration with Dr. Grof at Esalen, Tarnas interpreted the Grof dossier of LSD experiences in terms of "archetypal" astrology. Professor Tarnas has been celebrated by Grof partisans for correlating the four "perinatal matrices" of Grof's "cartography of the psyche" with "archetypal meanings" of the planets Neptune, Saturn, Pluto, and Uranus. Grof is reputed to have endorsed this linkage, implying that archetypal astrology is the only means for successfully predicting the content of experiences in LSD "psychotherapy," Holotropic Breathwork, and the "spontaneous eruption of unconscious contents." These superficial ideas, well known on the web, are in strong dispute elsewhere.

The "epochal transformation" proposed by Tarnas can be interpreted in terms of LSD psychotherapy, holotropic theory and hyperventilation, suppression of female dissidents, synchronicity theory, archetypal theory, and archetypal astrology. Citizens do not need the psychedelic indulgence preferred in lax academic ranks. There is still no compelling reason to abandon the traditional philosophical discipline (stretching back in variants to Plato) in favour of alternative post-1950s psychedelia and pseudo-holistic commerce. However, the Cartesian vivisection brutality, the Kantian cordon, Humean scepticism, and Nietzschean "will to power" can be regarded as impediments. The Aristotelian class system should long ago have been eliminated, instead surviving and flourishing in modern science and academic philosophy.

My own version of philosophy, which is citizen, differs very substantially from the current "Integral Studies" orientation favoured in American counterculture. I have attempted to illustrate that factor on this webpage. See also autobiographical reflections and Tarnas-Grof.

Kevin R. D. Shepherd

January 2011 (later partly modified)

Capra, Fritjof, The Hidden Connections (London: HarperCollins, 2002).

Castro, Stephen J., Hypocrisy and Dissent within the Findhorn Foundation (Forres: New Media, 1996).

Curry, E. P., "Carl Jung, Stanislav Grof, and New Age Medical Mysticism," The Scientific Review of Alternative Medicine (2002) 6(2):83-90.

Grof, Stanislav, The Adventure of Self-Discovery (State University of New York Press, 1988).

-----------Psychology of the Future (State University of New York Press, 2000).

Kant, Immanuel, Critique of Pure Reason, ed. V. Politis (London: Dent, 1934; new edn, 1993).

Kuehn, Manfred, Kant: A Biography (Cambridge University Press, 2001).

Magee, Bryan, The Great Philosophers (Oxford University Press, 1988).

------------The Story of Philosophy (London: Dorling Kindersley, 1998).

Russell, Bertrand, A History of Western Philosophy (1946; new edn, London: Routledge, 2000).

Shepherd, Kevin R. D., Psychology in Science (Cambridge: Anthropographia, 1983).

------------The Resurrection of Philosophy (Cambridge: Anthropographia, 1989).

------------Meaning in Anthropos: Anthropography as an Interdiscipinary Science of Culture (Cambridge: Anthropographia, 1991).

------------Some Philosophical Critiques and Appraisals (Dorchester: Citizen Initiative, 2004).

------------Pointed Observations (Dorchester: Citizen Initiative, 2005).

Sokal, Alan and Jean Bricmont, Fashionable Nonsense: Postmodern Intellectuals' Abuse of Science (London: Profile, 1998).

Sokal, Alan, Beyond the Hoax: Science, Philosophy, and Culture (Oxford University Press, 2008).

Tarnas, Richard, The Passion of the Western Mind (1991; repr. London: Pimlico, 1996).

------------Cosmos and Psyche: Intimations of a New World View (New York: Plume, 2006).